becoming cosmopolitan citizen-architects

II. Frystihúsið í Vogum | Eva Dögg Jóhannsdóttir

Reviving a corpse: an architectural thesis

Abstract

Adaptive reuse of former industrial spaces can offer unique settings for community and cultural events. Thus, providing a sense of continuity and identity for individuals and communities, preserving a tangible link to the past while creating new spaces for present and future use. It can also contribute to a sense of place attachment and social cohesion, as people gather and connect in shared spaces that hold historical and cultural significance while fostering a sense of pride within the community. The creation of cultural hubs with adaptive reuse can foster the development of new practices and traditions, creating a foundation for communities moving forward.

The village of Vogar, Iceland is a direct result of the fishing industry. The town’s fish processing facility (Icelandic: Frystihús) was paramount in counteracting the homestead sprawl and creating the conditions for a viable village. Constructed in 1941, it quickly became the area’s largest employer. The building and land were bought by the municipality in 2018 after being in disuse for some years. Most inhabitants have some form of personal connection to the building, and it is seen as a core of community identity. This thesis works with the fish processing facility and how it could continue to be a sturdy foundation for Vogar’s growth and continue to adapt with the community’s evolving wants and needs, while still linking to the past and its role in shaping Vogar.

- Introduction

- Context of ideas and theoretical exploration

- Methodology

- Findings

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

Introduction

We build with purpose. Inevitably, the built and the purpose no longer coincide. On the industrial level, the functions and scale of the built are not that of the human. Materials, machines, and processes shape industrial spaces. When industry leaves, the remnants, originally on the outskirts of urban centers, can find themselves surrounded in the human environment. We are left with unorthodox spaces and buildings to either disuse or adapt and reuse.

This is the conundrum being faced by the village of Vogar, in the southwest of Iceland. The now former fishing village stabilized, evolved, and grew from sparse homesteads toiling in rough conditions, to a thriving fishing village. The catalyst for this change was the construction of a fish processing facility in 1942 with a proper harbor two years later.1 For four decades fishing, fish processing, and fish freezing were the bread and butter of Vogar. The building was then sold to a fish farm and utilized for packaging before eventually falling into disuse and disrepair.2 In 2018 the town bought the land3 where the building stands, or more aptly, is crumbling today.

Vogar’s town council drew the conclusion that the building could not be saved, should be demolished, and something new built in its place.4 A strong local grassroots movement took matters into their own hands and contacted the Cultural Heritage Agency of Iceland in hopes that they could step in. This case was unusual for the CHAI, as most sites they work with are over 100 years old or have obvious national and cultural significance.5 But something about the building has a pull. Whether it is how integral it was to the town’s growth, how connected it is to the lives and memories of the area’s residents, or how interwoven the building is with the cultural identity and sense of place in Vogar. It might also have to do with how unpretentious the building itself is, with the seams of its many expansions evident, the multiplex of materials adorning its outer shell, and the concrete walls fractured and weathered. The twinkle in the eyes of those who know the building speaks to its potential to stay, to keep evolving, to become a foundation for Vogar once again. To do so more than the structure must change, but its purpose as well. How can the old fish processing facility become something new without losing itself in the process?

We build with purpose. Inevitably, the built and the purpose no longer coincide. On the industrial level, the functions and scale of the built are not that of the human. Materials, machines, and processes shape industrial spaces. When industry leaves, the remnants, originally on the outskirts of urban centers, can find themselves surrounded in the human environment. We are left with unorthodox spaces and buildings to either disuse or adapt and reuse.

This is the conundrum being faced by the village of Vogar, in the southwest of Iceland. The now former fishing village stabilized, evolved, and grew from sparse homesteads toiling in rough conditions, to a thriving fishing village. The catalyst for this change was the construction of a fish processing facility in 1942 with a proper harbor two years later.1 For four decades fishing, fish processing, and fish freezing were the bread and butter of Vogar. The building was then sold to a fish farm and utilized for packaging before eventually falling into disuse and disrepair.2 In 2018 the town bought the land3 where the building stands, or more aptly, is crumbling today.

Vogar’s town council drew the conclusion that the building could not be saved, should be demolished, and something new built in its place.4 A strong local grassroots movement took matters into their own hands and contacted the Cultural Heritage Agency of Iceland in hopes that they could step in. This case was unusual for the CHAI, as most sites they work with are over 100 years old or have obvious national and cultural significance.5 But something about the building has a pull. Whether it is how integral it was to the town’s growth, how connected it is to the lives and memories of the area’s residents, or how interwoven the building is with the cultural identity and sense of place in Vogar. It might also have to do with how unpretentious the building itself is, with the seams of its many expansions evident, the multiplex of materials adorning its outer shell, and the concrete walls fractured and weathered. The twinkle in the eyes of those who know the building speaks to its potential to stay, to keep evolving, to become a foundation for Vogar once again. To do so more than the structure must change, but its purpose as well. How can the old fish processing facility become something new without losing itself in the process?

1 Særún Jónsdóttir, “Merkisár í atvinnusögu sveitarfélagsins.”

2 Personal correspondence with Særún Jónsdóttir, daughter of former owner of the fish processing facility.

3 Ibid.

4 Þorvaldur Örn Árnason, “Vogarhöfn og svæðið umhverfis hannað til framtíðar.”

5 Lög um menningarminjar nr. 80/2012

Context of ideas and theoretical exploration

The fish processing facility has cemented itself as a cultural cornerstone of Vogar. For the oldest generation it might be what brought them to Vogar, where they spent much of their day. The next generation grew up knowing they had the possibility of a stable income in their hometown. Their adolescent memories of summer interwoven with the concrete walls and the repetitive movements of filleting fish. The younger generation listened to stories of either the glory days or the danger of the fishing industry while watching its physical remnants wither.6

The current community’s sense of identity and place are tightly intertwined with the old fish processing facility on top of the myriad of personal connections, especially within the older generation. Tom Borrup argues that attachment to place is not only social or aesthetic, but also built on individual experiences with the place. 7 He also points to feminist academics and literature (Maria Vittoria Guiliani, Leonie Sandercock, Ann Forsyth, Geraldine Pratt, Victoria Rosner) in not disregarding emotion and passion over the rational in cultural city planning.8 That “the basis for attachment is emotional rather than simply functional.”9

When grappling with the possibility of reusing and repurposing a building and wanting to layer on top of the multitude of personal connections within the local community, it can be difficult to comprehend the scale of time. Knowing that at some point the personal connections to the building as a fish processing facility will fade, are fading, and that the building and place must hold on to the potential for personal connection and attachment, to be a mnemonic for generations to come. 10

When telling me about growing up in Vogar, well after the fishing industry left, one woman recalled always taking an extra detour when her gym class was sent out to jog, just to check on the changes in deterioration of the building. In a way, the building’s façade becomes, as Aloïs Riegl defines it, an unintentional monument with age value.11 This input was an early indication for how to juggle the existing connections, stories, and memories while allowing the site to become something bigger than itself. To expand the familiar and show the “adjacent possibilities”.12

6 The lived experience of anyone in dying fishing villages (personal).

7 Borrup, The Power of Culture in City Planning, 116.

8 Borrup, The Power of Culture in City Planning, 109.

9 Borrup quoting Russel Belk, The Power of Culture in City Planning, 113.

10 Stone, UnDoing Buildings, 18.

11 Riegl, The Modern Cult of Monuments, 3.

12 Borrup quoting Steve Johnson, The Power of Culture in City Planning, 45

13 Ibid.

14 Brand, How Buildings Learn, 10.

15 Pétursdóttir, “Concrete Matters”, 37.

16 UNESCO, “World heritage.”

17 Borrup, The Power of Culture in City Planning, 3, 61.

18 Borrup, The Power of Culture in City Planning, 64.

19 Indriði Níelsson, “Hafnargata 101, minnisblað.”

20 Correspondance with the Cultural Heritage Agency of Iceland.

21 Ibid.

22 Brand, How Buildings Learn, 11.

23 Brand, How Buildings Learn, 23.

24 Brand, How Buildings Learn, 24.

25 Vogar.is

26 Fasteignaskrá, “Fasteignamat 2022.”

27 Hagstofan, “Mannfjöldi eftir sveitarfélagi, kyni og aldri 1. desember 1997-2022.”

28 Hagstofan, “Innflytjendur eftir kyni og sveitarfélagi 1. janúar 1996-2022.”

“… We must make a distinction between our perception of the localized historical memories it contains and the more general awareness of the passage of time, … survival over time, and the visible traces of age.” 13

In other words, age, and the act of aging is “what makes buildings come to be loved”. 14

When working with age, inevitably one must touch on preservation and heritage. Here one can go into the debate of the tangible vs. intangible and whether heritage simply is or whether it is cultivated and curated. 15 Heritage as defined by UNESCO “is our legacy from the past, what we live with today, and what we pass on to future generations.”16 Here I want to take some liberties and (over)simplify heritage to “what was”. I am seeking inspiration from Tom Borrup’s definition of culture as being “way of [living daily] life”. 17 Culture is therefore both how we interact with heritage and how we divert from it in our daily lives. It is how we construct a collective identity. 18

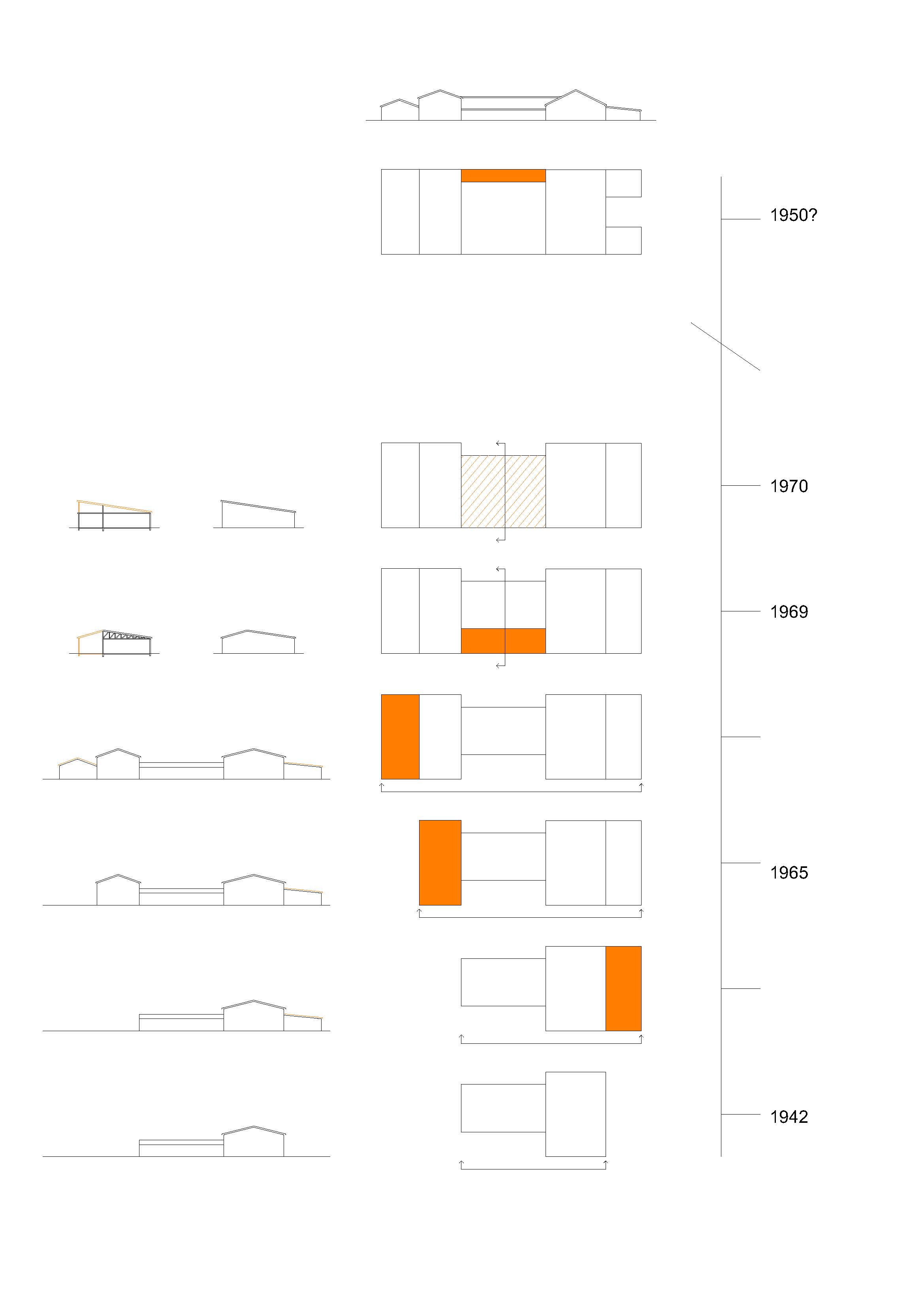

![Figure 2 - Historical evolution of the fish processing facility]()

In the introduction I recounted how the CHAI came to be involved with the project, after being contacted by a grassroots movement in Vogar (Minja- og sögufélags Vatnsleysustrandar, MSV). Two representatives from the CHAI went out to have a look at the site. The town council had previously hired an engineer to do a building survey to assess the amount of damage to the structure. The survey concludes thusly “the buildings are unusable... [so part of the building] should be torn down immediately... [and] what is salvageable would be too costly to restore and should therefore also be torn down.” 19 When the CHAI representatives looked around the building, they simply said “we have seen much worse [conditions for successful projects] before.” 20

As stated before, this project would not normally fall under the authority of the CHAI. Although it is fully within their power to put a house under a conservation status if they see fit, they do so sparingly and only when they see strong reason to. As of this paper, they do not feel they can justify such an action. 21

This is not necessarily a terrible thing. If Stewart Brand is correct then on the building’s lifespan between new and corpse, we are at “the unappreciated, undocumented, awkward seeming time when it [the building is] alive to evolution... [and] those are the best years.”22 Although, if the trajectory of the building is not changed soon then realistically, we are on the verge of the corpse stage. There is freedom here, reinforced further by categorizing the building as “low road”-ish. 23 The -ish, although highly unacademic, is meant to convey that the building is much closer on the spectrum to “low road” than to “high road.” It fulfills the aspect of “nobody cares what you do in there” but not the aspect of being “low visibility,” with the point of “no style” up for debate. 24 The constricting connotation with preservation is therefore irrelevant. I feel that that the old fish processing facility, with its many stages of evolution already under its belt, is much better suited to an adaptive reuse approach.

Here it is important to look at the predicted population growth in the area. As of February 2023, Vogar has 1408 inhabitants25 and is the municipality predicted to see the largest growth in population percentage wise within Iceland in the next few years. Property prices in Vogar are similar to their neighboring municipalities but substantially lower than the nearby capital area. 26 With a sizable portion of new builds being smaller apartments, it is likely that the area will attract middle to lower income individuals and families. The Reykjanes Peninsula has a higher percentage of immigrants than is average for Iceland,27 with Vogar’s immigrant population almost doubling in size within the last five years.28 This demographic (which is in no way homogeneous) should also be considered when working with the old fish processing facility. As it is not simply a monument to the past, but meant as a place for community, for culture, for bringing together and sharing.

When working with age, inevitably one must touch on preservation and heritage. Here one can go into the debate of the tangible vs. intangible and whether heritage simply is or whether it is cultivated and curated. 15 Heritage as defined by UNESCO “is our legacy from the past, what we live with today, and what we pass on to future generations.”16 Here I want to take some liberties and (over)simplify heritage to “what was”. I am seeking inspiration from Tom Borrup’s definition of culture as being “way of [living daily] life”. 17 Culture is therefore both how we interact with heritage and how we divert from it in our daily lives. It is how we construct a collective identity. 18

In the introduction I recounted how the CHAI came to be involved with the project, after being contacted by a grassroots movement in Vogar (Minja- og sögufélags Vatnsleysustrandar, MSV). Two representatives from the CHAI went out to have a look at the site. The town council had previously hired an engineer to do a building survey to assess the amount of damage to the structure. The survey concludes thusly “the buildings are unusable... [so part of the building] should be torn down immediately... [and] what is salvageable would be too costly to restore and should therefore also be torn down.” 19 When the CHAI representatives looked around the building, they simply said “we have seen much worse [conditions for successful projects] before.” 20

As stated before, this project would not normally fall under the authority of the CHAI. Although it is fully within their power to put a house under a conservation status if they see fit, they do so sparingly and only when they see strong reason to. As of this paper, they do not feel they can justify such an action. 21

This is not necessarily a terrible thing. If Stewart Brand is correct then on the building’s lifespan between new and corpse, we are at “the unappreciated, undocumented, awkward seeming time when it [the building is] alive to evolution... [and] those are the best years.”22 Although, if the trajectory of the building is not changed soon then realistically, we are on the verge of the corpse stage. There is freedom here, reinforced further by categorizing the building as “low road”-ish. 23 The -ish, although highly unacademic, is meant to convey that the building is much closer on the spectrum to “low road” than to “high road.” It fulfills the aspect of “nobody cares what you do in there” but not the aspect of being “low visibility,” with the point of “no style” up for debate. 24 The constricting connotation with preservation is therefore irrelevant. I feel that that the old fish processing facility, with its many stages of evolution already under its belt, is much better suited to an adaptive reuse approach.

Here it is important to look at the predicted population growth in the area. As of February 2023, Vogar has 1408 inhabitants25 and is the municipality predicted to see the largest growth in population percentage wise within Iceland in the next few years. Property prices in Vogar are similar to their neighboring municipalities but substantially lower than the nearby capital area. 26 With a sizable portion of new builds being smaller apartments, it is likely that the area will attract middle to lower income individuals and families. The Reykjanes Peninsula has a higher percentage of immigrants than is average for Iceland,27 with Vogar’s immigrant population almost doubling in size within the last five years.28 This demographic (which is in no way homogeneous) should also be considered when working with the old fish processing facility. As it is not simply a monument to the past, but meant as a place for community, for culture, for bringing together and sharing.

Methodology

The first time Vogar’s fish processing facility was brought to my attention was in a lecture on the Reykjanes region by the CHAI. I fell for the building, and it took up residence in the back of my mind, until the time to decide on a final project was upon us.

The initial stage of the project consisted of researching Vogar, its history, culture, growth, demographics, and the impact of the fish processing facility on the town. This information was then mapped. Research into the building itself was also conducted at this stage. Plans from varying stages of its history were collected and traced, enabling a fuller view of the existing building and its changes through time. As not all parts of the building had available and accessible plans, a site visit was conducted.

At this stage I looked into different case studies of similar projects. In the Icelandic context I reviewed a mix of demolished buildings, low- road, and high- road approaches to industrial buildings of a similar age, particularly within the fishing industry. In the instances of demolished buildings, I also investigated what they were replaced with. In the international context I decided to view case studies for adaptive reuse projects as opposed to preservation projects.

A meeting with the CHAI was held, to learn more about their connection to the project and to gain access to the information they had already gathered. Through this meeting I was given contact information of the head members of the grassroots movement in Vogar (Minja- og sögufélags Vatnsleysustrandar, MSV). One of these contacts was the daughter of the original owner of the fish processing facility. She was able to give me access to an array of personal documents and anecdotes spanning the entire history of the facility.

I was invited to a meeting with the members of the MSV in Vogar. They were able to give further information on the plans which had been drawn up, as well as giving information on varying stages of the building’s development. Interviews with locals, former residents, and employees of the municipality residing elsewhere were conducted. I tried speaking with a diverse group of individuals, ranging from elderly who had lived in Vogar from birth to immigrant children who had moved to Vogar within the last few years.

I also reviewed relevant literature pertaining to adaptive reuse, connection to place, culture in planning and design, heritage, and preservation.

The first time Vogar’s fish processing facility was brought to my attention was in a lecture on the Reykjanes region by the CHAI. I fell for the building, and it took up residence in the back of my mind, until the time to decide on a final project was upon us.

The initial stage of the project consisted of researching Vogar, its history, culture, growth, demographics, and the impact of the fish processing facility on the town. This information was then mapped. Research into the building itself was also conducted at this stage. Plans from varying stages of its history were collected and traced, enabling a fuller view of the existing building and its changes through time. As not all parts of the building had available and accessible plans, a site visit was conducted.

At this stage I looked into different case studies of similar projects. In the Icelandic context I reviewed a mix of demolished buildings, low- road, and high- road approaches to industrial buildings of a similar age, particularly within the fishing industry. In the instances of demolished buildings, I also investigated what they were replaced with. In the international context I decided to view case studies for adaptive reuse projects as opposed to preservation projects.

A meeting with the CHAI was held, to learn more about their connection to the project and to gain access to the information they had already gathered. Through this meeting I was given contact information of the head members of the grassroots movement in Vogar (Minja- og sögufélags Vatnsleysustrandar, MSV). One of these contacts was the daughter of the original owner of the fish processing facility. She was able to give me access to an array of personal documents and anecdotes spanning the entire history of the facility.

I was invited to a meeting with the members of the MSV in Vogar. They were able to give further information on the plans which had been drawn up, as well as giving information on varying stages of the building’s development. Interviews with locals, former residents, and employees of the municipality residing elsewhere were conducted. I tried speaking with a diverse group of individuals, ranging from elderly who had lived in Vogar from birth to immigrant children who had moved to Vogar within the last few years.

I also reviewed relevant literature pertaining to adaptive reuse, connection to place, culture in planning and design, heritage, and preservation.

Findings

Vogar is at a crossroads, both regarding their overall town as well as the fish processing facility. They reap the benefits of living between the capital area and Reykjanesbær, where the international airport of Iceland is located. This has made the lack of some amenities tolerable. In a way this geographical location also becomes a hinderance, as the threshold for when to make changes is higher. An example of this would be the recent addition of a grocery store early this year.29 The newest information, other than the recently opened grocery store in Vogar is from 1987.30 Between these two stores, Vogar’s inhabitants had to go to the next town over for food.

![Figure 3 - Amenities map]()

If we map the cultural amenities in Vogar31 we see that the town can provide education on the preschool and grade school level, up to age 16. After this families must look outside the municipality for further education. The closest secondary school/high school is not too far away, 15 km in one direction and another 24 km away.

Commuting possibilities become a limiting factor. Walking and cycling are unrealistic. The bus commute to the closer school is 45 minutes and the other 37 minutes,32 which is on par with some bus commutes to school within the capitol area.33 The other option would be to utilize a car. The legal age for a driving license in Iceland is 17 years.34 They would therefore still be reliant on other traveling arrangements the first year. After that they could drive to school themselves, if it is within the student´s means to get a license, a car, and fuel. These commute options allow for the possibility of the students to keep living at home, an option that is not realistic for many Icelandic communities.

If we look at the amenities map again, you can see that many of them are close to or on the main road into town. If we follow the main road, we see the public swimming pool and sports hall next to the town park, where the town holds an annual summer festival named family days (Icelandic: fjölskyldudagar). Across the road is the town’s pond followed by the harbor area, where the fish processing facility is. Locals report that when newcomers or tourists drive into town, they will usually follow the road all the way out to the tip of the coastal defense structure.

![Figure 4: The coastal defense structure creating Vogar’s harbor.]()

On the last night of Vogar´s summer festival a show is held in the village park. It is tradition that a house in each neighborhood, which is color coded and decorated for the week, holds a party afterwards for the rest of the neighborhood. I don’t know how sustainable this practice will be in the future though, with the growth of the town. How they will keep this open and friendly tradition of letting the entire neighborhood into one’s house, especially with the expected rate of newcomers. There are three places in town to hold larger indoor gatherings: the sports hall (569m2),34 the school cafeteria (200m2),37 and the elderly care home (110m2).36 These options are merely tolerable. But they do not feel as though they inhabit a feeling of place, of Vogar. The house parties feel more like Vogar, its community, its people.

This is where the fish processing facility could fill in the gap. It is so entrenched in the community of Vogar that it can work as an extension of the community itself. The opening of the building for community events then acts as a ceremonial signifier for welcoming newcomers into the community. As the old fish processing facility is within 400m of the park its location could easily become a natural extension of the summer festival. This was in many ways the opening to my project. Then the question of the other 51 weeks of the year is brought up. A space large and grand enough to be incorporated in a summer festival also has the ability to hold other festivities: weddings, company parties, the traditional Icelandic Þorrablót etc. With the addition of a stage musical events and stage performances become possible. At present, there isn’t an ideal place in town to have a theatre performance. One former local spoke of how active the youth drama club was when she was young. A current local told me that it had all but died out. Creating a space which allows for the possibility could reinvigorate these activities.

What about the day to day; the smaller moments? After interviews with locals, both current and former, an idea of what the village needs starts to emerge. There is a restaurant in town which regularly goes under, closes, and is then reopened. Other than that, there are not really any public indoor spaces to meet up, hang out, or spend time. Restaurants also aren´t known for their ‘stay as long as you would like’ atmosphere. Although, food is a great way to encourage interpersonal connection.38 Programing for the fish processing facility must then incorporate a space which allows for food and longer periods to linger, such as a café. Creating local job positions and during the busier summer season, a new type of summer job for students. With the addition of a kid’s area, it could become a place for parents with younger children to meet up. Students would have a place to study during finals outside of their home but within their community. Going further, the upper level of the café would accommodate those seeking a quieter area to work. With smaller rentable rooms, both short and long term, and an open area where groups could work without being disturbed.

This programing, simply put, would occupy the footprint of the building as it stands today. There would need to be some work done to get the building up to code and safety regulations, but I am not working outside of the footprint of the current structure. This is not because there shouldn’t be any additions made or the footprint couldn’t or shouldn’t be bigger. It is purely a pragmatic decision. The research I have done points to the building and community being able to sustain this programing within these parameters. If we look at the different stages and changes made to the building in the past, we see that an expansion is added only when the current use has outgrown the space it occupied. As an adaptive reuse approach is being taken, the programing must inform the design. The purpose of this design is to breathe life back into the building; to facilitate the coming of spring, for leaves to grow anew, for a new ring in the trunk, to make sure that the building does not become a corpse.

![Figure 5: Drawings showcasing changes. Current section bottom. Proposal top.]()

There are parts of the building that cannot be salvaged, in the sense that it cannot be reutilized as a stable building element. Unlike a tree, it is not a dead or diseased limb that must be removed so the rest of the organism can prosper. At least, not everything. The broken glass and rotted wood roof may be removed. The damaged beyond repair concrete and pumice brick walls can stay. They can be a testament to the age of the building. They can show what would have happened if a different path for the building was chosen. If nothing had been saved. In this way, the connection to the past is kept. The evolution of the building is not so drastic as to cut the connection already in place for so many locals. Not so drastic that they lose their feeling of ownership. They can walk by the building with their children and say: this building was falling down, like this wall here, but we saved it.

Another way I wanted to work with the connection to the past, other than materiality, was in utilizing sightlines. When changing the usage of a building from industrial to a social and communal one, there must still be a connection to the former purpose of the structure. The clearest direction would be a connection to fish and boats or to the ocean. At present, the coastal defense structure shielding the building from the often-tumultuous ocean waves, also blocks one’s line of sight to the ocean and the horizon. The harbor, situated next to the fish processing facility, does give access to the ocean, both physically and visually, but the purpose of the defense structure which shapes the harbor is fulfilled and the small patch of ocean is tame and domesticated. As the new programing called for a new entrance to the building, it felt right to evoke the connection to the ocean at the moment of entering. A break in the coastal defense structure, must be created to accomplish this effect. The breach is then filled with a pavilion.

Concrete walls on either side of the opening hold the stones of the coastal defenses back while connecting to the original building’s material. The pavilion slopes down towards the ocean, where a glass wall becomes the new border between land and sea. When interacting only with the main building, this view is only available right at the start of the journey into the building; before one must then turn to either side to the social functions within.

![Figure 6: Render of new entrance. Shows line of sight.]()

Vogar is at a crossroads, both regarding their overall town as well as the fish processing facility. They reap the benefits of living between the capital area and Reykjanesbær, where the international airport of Iceland is located. This has made the lack of some amenities tolerable. In a way this geographical location also becomes a hinderance, as the threshold for when to make changes is higher. An example of this would be the recent addition of a grocery store early this year.29 The newest information, other than the recently opened grocery store in Vogar is from 1987.30 Between these two stores, Vogar’s inhabitants had to go to the next town over for food.

If we map the cultural amenities in Vogar31 we see that the town can provide education on the preschool and grade school level, up to age 16. After this families must look outside the municipality for further education. The closest secondary school/high school is not too far away, 15 km in one direction and another 24 km away.

Commuting possibilities become a limiting factor. Walking and cycling are unrealistic. The bus commute to the closer school is 45 minutes and the other 37 minutes,32 which is on par with some bus commutes to school within the capitol area.33 The other option would be to utilize a car. The legal age for a driving license in Iceland is 17 years.34 They would therefore still be reliant on other traveling arrangements the first year. After that they could drive to school themselves, if it is within the student´s means to get a license, a car, and fuel. These commute options allow for the possibility of the students to keep living at home, an option that is not realistic for many Icelandic communities.

If we look at the amenities map again, you can see that many of them are close to or on the main road into town. If we follow the main road, we see the public swimming pool and sports hall next to the town park, where the town holds an annual summer festival named family days (Icelandic: fjölskyldudagar). Across the road is the town’s pond followed by the harbor area, where the fish processing facility is. Locals report that when newcomers or tourists drive into town, they will usually follow the road all the way out to the tip of the coastal defense structure.

On the last night of Vogar´s summer festival a show is held in the village park. It is tradition that a house in each neighborhood, which is color coded and decorated for the week, holds a party afterwards for the rest of the neighborhood. I don’t know how sustainable this practice will be in the future though, with the growth of the town. How they will keep this open and friendly tradition of letting the entire neighborhood into one’s house, especially with the expected rate of newcomers. There are three places in town to hold larger indoor gatherings: the sports hall (569m2),34 the school cafeteria (200m2),37 and the elderly care home (110m2).36 These options are merely tolerable. But they do not feel as though they inhabit a feeling of place, of Vogar. The house parties feel more like Vogar, its community, its people.

This is where the fish processing facility could fill in the gap. It is so entrenched in the community of Vogar that it can work as an extension of the community itself. The opening of the building for community events then acts as a ceremonial signifier for welcoming newcomers into the community. As the old fish processing facility is within 400m of the park its location could easily become a natural extension of the summer festival. This was in many ways the opening to my project. Then the question of the other 51 weeks of the year is brought up. A space large and grand enough to be incorporated in a summer festival also has the ability to hold other festivities: weddings, company parties, the traditional Icelandic Þorrablót etc. With the addition of a stage musical events and stage performances become possible. At present, there isn’t an ideal place in town to have a theatre performance. One former local spoke of how active the youth drama club was when she was young. A current local told me that it had all but died out. Creating a space which allows for the possibility could reinvigorate these activities.

What about the day to day; the smaller moments? After interviews with locals, both current and former, an idea of what the village needs starts to emerge. There is a restaurant in town which regularly goes under, closes, and is then reopened. Other than that, there are not really any public indoor spaces to meet up, hang out, or spend time. Restaurants also aren´t known for their ‘stay as long as you would like’ atmosphere. Although, food is a great way to encourage interpersonal connection.38 Programing for the fish processing facility must then incorporate a space which allows for food and longer periods to linger, such as a café. Creating local job positions and during the busier summer season, a new type of summer job for students. With the addition of a kid’s area, it could become a place for parents with younger children to meet up. Students would have a place to study during finals outside of their home but within their community. Going further, the upper level of the café would accommodate those seeking a quieter area to work. With smaller rentable rooms, both short and long term, and an open area where groups could work without being disturbed.

This programing, simply put, would occupy the footprint of the building as it stands today. There would need to be some work done to get the building up to code and safety regulations, but I am not working outside of the footprint of the current structure. This is not because there shouldn’t be any additions made or the footprint couldn’t or shouldn’t be bigger. It is purely a pragmatic decision. The research I have done points to the building and community being able to sustain this programing within these parameters. If we look at the different stages and changes made to the building in the past, we see that an expansion is added only when the current use has outgrown the space it occupied. As an adaptive reuse approach is being taken, the programing must inform the design. The purpose of this design is to breathe life back into the building; to facilitate the coming of spring, for leaves to grow anew, for a new ring in the trunk, to make sure that the building does not become a corpse.

There are parts of the building that cannot be salvaged, in the sense that it cannot be reutilized as a stable building element. Unlike a tree, it is not a dead or diseased limb that must be removed so the rest of the organism can prosper. At least, not everything. The broken glass and rotted wood roof may be removed. The damaged beyond repair concrete and pumice brick walls can stay. They can be a testament to the age of the building. They can show what would have happened if a different path for the building was chosen. If nothing had been saved. In this way, the connection to the past is kept. The evolution of the building is not so drastic as to cut the connection already in place for so many locals. Not so drastic that they lose their feeling of ownership. They can walk by the building with their children and say: this building was falling down, like this wall here, but we saved it.

Another way I wanted to work with the connection to the past, other than materiality, was in utilizing sightlines. When changing the usage of a building from industrial to a social and communal one, there must still be a connection to the former purpose of the structure. The clearest direction would be a connection to fish and boats or to the ocean. At present, the coastal defense structure shielding the building from the often-tumultuous ocean waves, also blocks one’s line of sight to the ocean and the horizon. The harbor, situated next to the fish processing facility, does give access to the ocean, both physically and visually, but the purpose of the defense structure which shapes the harbor is fulfilled and the small patch of ocean is tame and domesticated. As the new programing called for a new entrance to the building, it felt right to evoke the connection to the ocean at the moment of entering. A break in the coastal defense structure, must be created to accomplish this effect. The breach is then filled with a pavilion.

Concrete walls on either side of the opening hold the stones of the coastal defenses back while connecting to the original building’s material. The pavilion slopes down towards the ocean, where a glass wall becomes the new border between land and sea. When interacting only with the main building, this view is only available right at the start of the journey into the building; before one must then turn to either side to the social functions within.

29 Sigurbjörn Daði Dagbjartsson, “Vogus opnar í Vogum.”

30 “Kaupfélag Suðurnesja – breytt símanúmer frá 1. Júlí.”

31 Borrup, The Power of Culture in City Planning, 74.

32 Strætó bs., “Route planner.”

33 Personal experience.

34 Samgöngustofan, “Ökunámi: Spurt og svarað.”

35 VT Teiknistofan HF, Íþróttamiðstöð, hafnargata 190 Vogar.

36 THG Arkitektar, Stóru Vogaskóli, Vogum Vatnsleysuströnd.

37 Guðrún Jónsdóttir, Heimilisvernd, Stórheimili að Akurgerði 25, Vogum Vatnsleysuströnd.

38 Borrup, The Power of Culture in City Planning, 12

Conclusion

The village of Vogar, Iceland, presents a unique case study of how adaptive reuse can help preserve community identity and foster social cohesion. As a small village, Vogar could easily get lost between the larger towns around it. It therefore becomes extremely important to cultivate a sense of identity and pride. With the influx of new homes being built and residents set to move in, the cultural identity of Vogar will no doubt shift. While it is important to welcome the new in, it is usually more successful to graft onto something older and more stable.

The old fish processing facility in Vogar would hardly classify as stable in the traditional structural or economic sense of the word. It does, however, have the unique factor of being irrevocably linked to the history, culture, and sense of place within Vogar. Cultivating this connection opens a new avenue to build upon. By shifting to a cultural and emotional approach, it suddenly becomes feasible to reestablish the old fish processing facility back into the daily fabric of Vogar’s community. The attachment and personal connection to the building that is already in place is preserved, creating the potential for a sense of continuity for future generations.

By repurposing the building, Vogar can continue to adapt with the community’s evolving wants and needs while fostering the development of new practices and traditions, thus creating a foundation for communities moving forward. This in turn can create sustainable, resilient communities that hold onto their cultural identity and sense of place. The building’s facade becomes a tangible reminder of the town’s history and cultural identity. The shelter within the building can provide a space for community events, cultural activities, and new businesses, all while preserving its historical and cultural significance.

Vogar has in its hands the opportunity to create strong social cohesion within its community by utilizing a building that is thoroughly interwoven with the emotions and memories of its residence. A place that can provide opportunities for future generations to live, interact, and create memories. In doing so, strengthening the very essence of the town. The fish processing facility still has the capacity to be a foundation for Vogar’s growth. All they have to do is revive it.

Bibliography

Books and articles

Borrup Tom. The power of culture in city planning. New York: Routledge, 2021.

Brand, Stewart. How buildings learn: what happens after they’re built. London: Phoenix Illustrated, 1997.

B. Plevoets & K. Van Cleempoel. “Adaptive reuse as a strategy towards conservation of cultural heritage: a literature review” in Structural Studies, Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage Architecture XII. WIT Press, 2011.

Riegl, Aloïs. “The modern cult of monuments: its characteristics and its origin.” Trans. Kurt W. Forster and Diane Ghirardo. Oppositions, 25 (1982), 21-51.

Stone, Sally. UnDoing Buildings: Adaptive Reuse and Cultural Memory. Routledge, 2019.

Þóra Pétursdóttir. “Concrete matters: Ruins of modernity and the things called heritage.” Journal of social archeology, 13,1 (2012): 31-53.

News articles

“Kaupfélag Suðurnesja – breytt símanúmer frá 1. Júlí.” Advert. Víkurfréttir. June 25th, 1987. https://timarit.is/page/6743099#page/n7/mode/2up.

Sigurbjörn Daði Dagbjartsson, (Vogus opnar í Vogum.” Víkurfréttir. March 11th, 2023. https://www.vf.is/frettir/vogus-opnar-i-vogum.

Þorvaldur Örn Árnason, “Vogahöfn og svæðið umhverfis hannað til framtíðar.” Víkurfréttir. July 9th, 2022. https://www.vf.is/adsent/vogahofn-og-svaedid-umhverfis-hannad-til-framtidar.

Architectural drawings

Bergmann Þorleifsson (master carpenter). Hafnargata 101, H/F Vogar, Vogar - Extension to south and changes to roof. Floor plan, section, elevation. (July 25th, 1969). https://teikningar.vogar.is/Hafnargata/Hafnarg.%20101_22.5.19.pdf.

— Hafnargata 101, H/F Vogar, Vogar - Changes to exterior of fish processing facility. Floor. plan, section, elevation. (September 7th, 1965). https://teikningar.vogar.is/Hafnargata/Hafnarg.%20101_22.5.190004.pdf.

Extension to fish freezing facility H/F Vogar, Vogum. South elevation and floor plan. (n.d.). https://teikningar.vogar.is/Hafnargata/Hafnarg.%20101_22.5.190002.pdf.

Guðrún Jónsdóttir (architect). Heimilisvernd, Stórheimili að Akurgerði 25, Vogum Vatnsleysuströnd. Drawing set nr 2. Floor plan. (January 2009). https://teikningar.vogar.is/Akurger%C3%B0i/Akurgerdi%2025.2.4.190001.pdf.

Rögnvaldur Johnsen (structural designer), Sölumiðstöð Hraðfrystihúsanna, tæknideild. Vogar H/F extension. North, west, and east elevation, floor plan, section, detail, site plan. (January 1st, 1965). https://teikningar.vogar.is/Hafnargata/Hafnarg.%20101_22.5.190003.pdf.

THG Arkitektar (architecture studio). Stóru Vogaskóli, Vogum Vatnsleysuströnd - Extension to the west. Floor plan. https://teikningar.vogar.is/Tjarnargata/Storu-Vogaskoli.pdf.

Verkfræðistofa Suðurnesja HF. Lóðarblað (Plot sheet). Document nr 3713. (Approved September 8th, 1991). https://teikningar.vogar.is/Hafnargata/Hafnarg.%20101_22.5.190001.pdf.

VT Teiknistofan HF (design studio). Íþróttamiðstöð, hafnargata 190 Vogar. Drawing set nr 6. Floor plan. (August 1992). https://teikningar.vogar.is/Hafnargata/Hafnarg.17_21.5.190008.pdf.

Other

Homepage of the municipality of Vogar. Accessed April 29th, 2023. https://www.vogar.is/.

“Fasteignamat 2022.” Fasteignaskrá. Accessed April 7th, 2023. https://fasteignaskra.is/fasteignir/fasteignamat/2022/.

Indriði Níelsson. Hafnargata 101: minnisblað. Ástandsskoðun mannvirkis (trans. Building survey by engineer). Verkís, April 27th, 2022.

“Innflytjendur eftir kyni og sveitarfélagi 1. janúar 1996-2022.” Hagstofan. Accessed April 7th, 2023. https://px.hagstofa.is/pxis/pxweb/is/Ibuar/Ibuar__mannfjoldi__3_bakgrunnur__Uppruni/MAN43005.px.

Lög um menningarminjar nr. 80/2012. Law. https://www.althingi.is/lagas/nuna/2012080.html.

“Mannfjöldi eftir sveitarfélagi, kyni og aldri 1. desember 1997-2022.” Hagstofan. Accessed April 7th, 2023. https://px.hagstofa.is/pxis/pxweb/is/Ibuar/Ibuar__mannfjoldi__2_byggdir__sveitarfelog/MAN09000.px.

Strætó bs. “Route planner.” Route planned for departure from Vogar with destination Flensborg and arrival at 8:10 on May 2nd, 2023. Accessed April 29th, 2023. https://straeto.is/en/route-planner/search/6bcef01de591.

— departure from Vogar with destination Fjölbrautarskóli Suðurnesja and arrival at 8:10 on May 2nd, 2023. Accessed April 29th, 2023https://straeto.is/en/route-planner/search/839d54b942e7.

Særún Jónsdóttir. “Merkisár í atvinnusögu sveitarfélagsins: 80 ár frá stofnun Voga hf.” Document sent via email. (2022).

UNESCO. “World Heritage.” Accessed April 8th, 2023. https://whc.unesco.org/en/about/#:~:text=Heritage%20is%20our%20legacy%20from,sources%20of%20life%20and%20inspiration.

“Ökunámi: Spurt og svarað.” Samgöngustofan. Accessed April 25th, 2023. https://www.samgongustofa.is/umferd/nam-og-rettindi/okunam/spurt-og-svarad/.

List of figures

Figure 1: Rafn Sigurbjörnsson (Landscape and Nature Documentary Photographer). Aerial photograph of fish processing facility in Vogar. 2022.

Figure 2: Eva Dögg Jóhannsdóttir. Diagram showing timeline of different stages of Vogar fish processing facility. 2023.

Figure 3: Eva Dögg Jóhannsdóttir. Map showing amenities in Vogar. 2023.

Figure 4: Eva Dögg Jóhannsdóttir. Photograph of Vogar harbor. 2023.

Figure 5: Eva Dögg Jóhannsdóttir. Architectural drawings from project. 2023.

Figure 6: Eva Dögg Jóhannsdóttir. Rendering of entrance to building. 2023.