becoming cosmopolitan citizen-architects

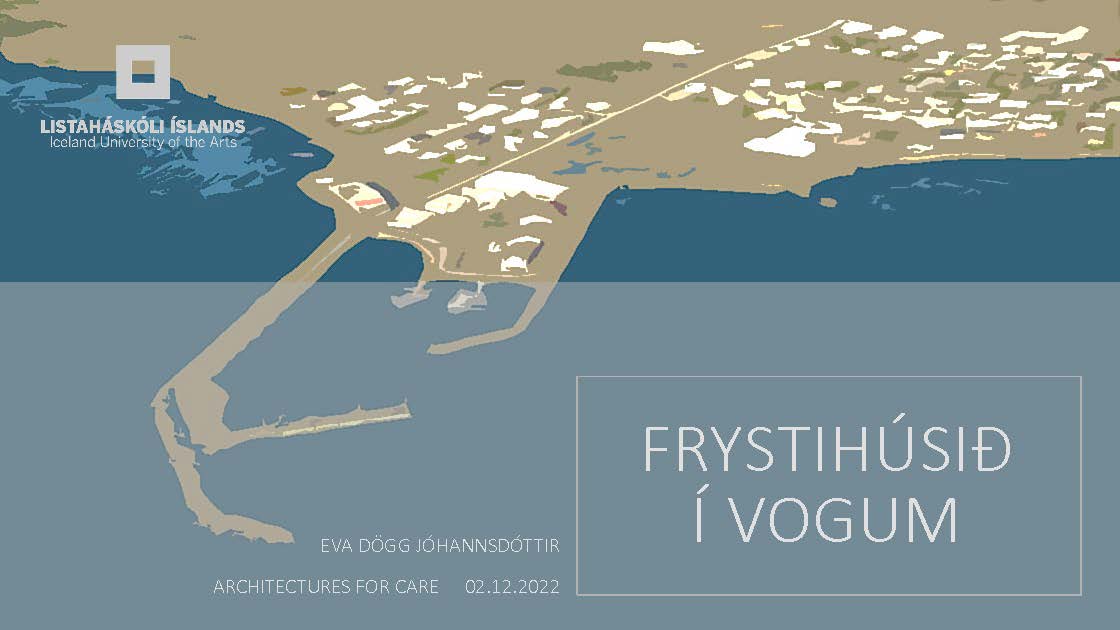

II. Frystihúsið í Vogum | Eva Dögg Jóhannsdóttir

Research Phase / Creating the Design Brief

After the initial research of Reykjanes phase, we moved towards shaping our individual M.Arch projects. This included finding a problem, justifying its importance and creating a design brief to deal with the issue. Here you can find my presentation of the work done prior to the actual M.Arch final project.

This phase of the project was presented on december 2nd 2022 for an open house at Kvikan community center in Grindavík Iceland.

Here you can see the entire project in a slideshow format.

For more information on individual slides, scroll down.

To start off we will go over some of my personal background. This will give you an idea of how I decided on this project and what lens, or biases, I view it through. The project is then placed within a larger context, to illustrate what framework is being worked within. The project itself is then introduced, followed by an urban study of the town Vogar. Finally, we look at the possible scenarios for the project going forward.

I was going to start off by introducing the importance of hafnarmenningu (e. harbour culture) in Iceland. My grandfather would bring me, or another grandchild, down to the harbour on weekends to look at the ships. Since I didn’t live in Iceland for most of my childhood, these visits where few and far between. I dreaded them. I suffer from motion sickness and my grandfather would blast opera music in the car while telling me the history of the ships.

I was going to have a picture of me and my grandfather or father down by the docks, but alas, a photo was not found so the image above must suffice.

The lack of a personal image was not for a lack of trying. I did find these two images from my father’s Facebook page where he is close to or on a harbour.

My family and I moved back to Iceland when I was eleven. We settled down on the east coast in the village of Reyðarfjörður. With a population around 1000, it is fairly small, and one might wonder why we moved there. The newly built aluminium factory was why. The population “boom” around the aluminium factory is not the first in Reyðarfjörður’s history though.

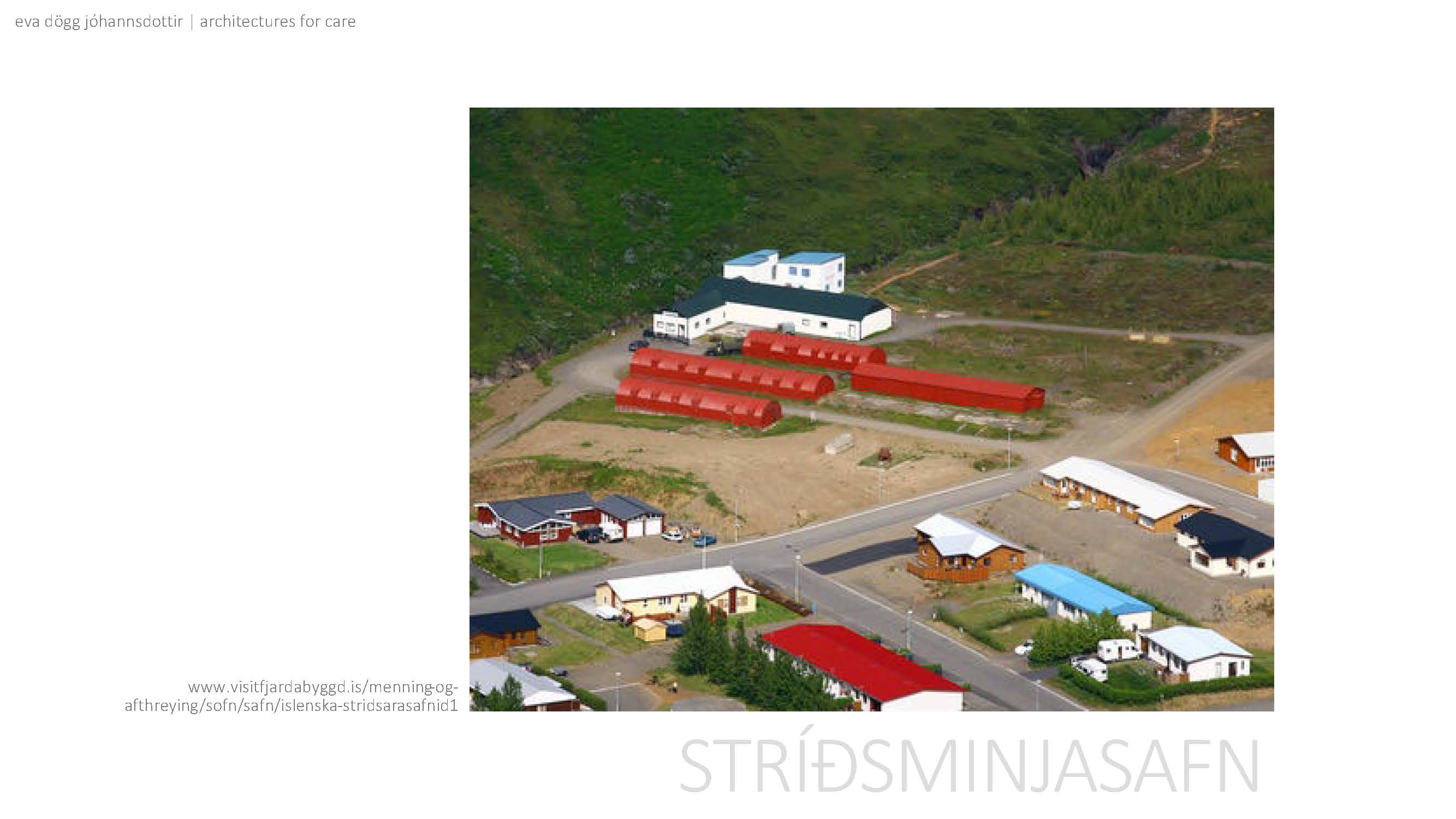

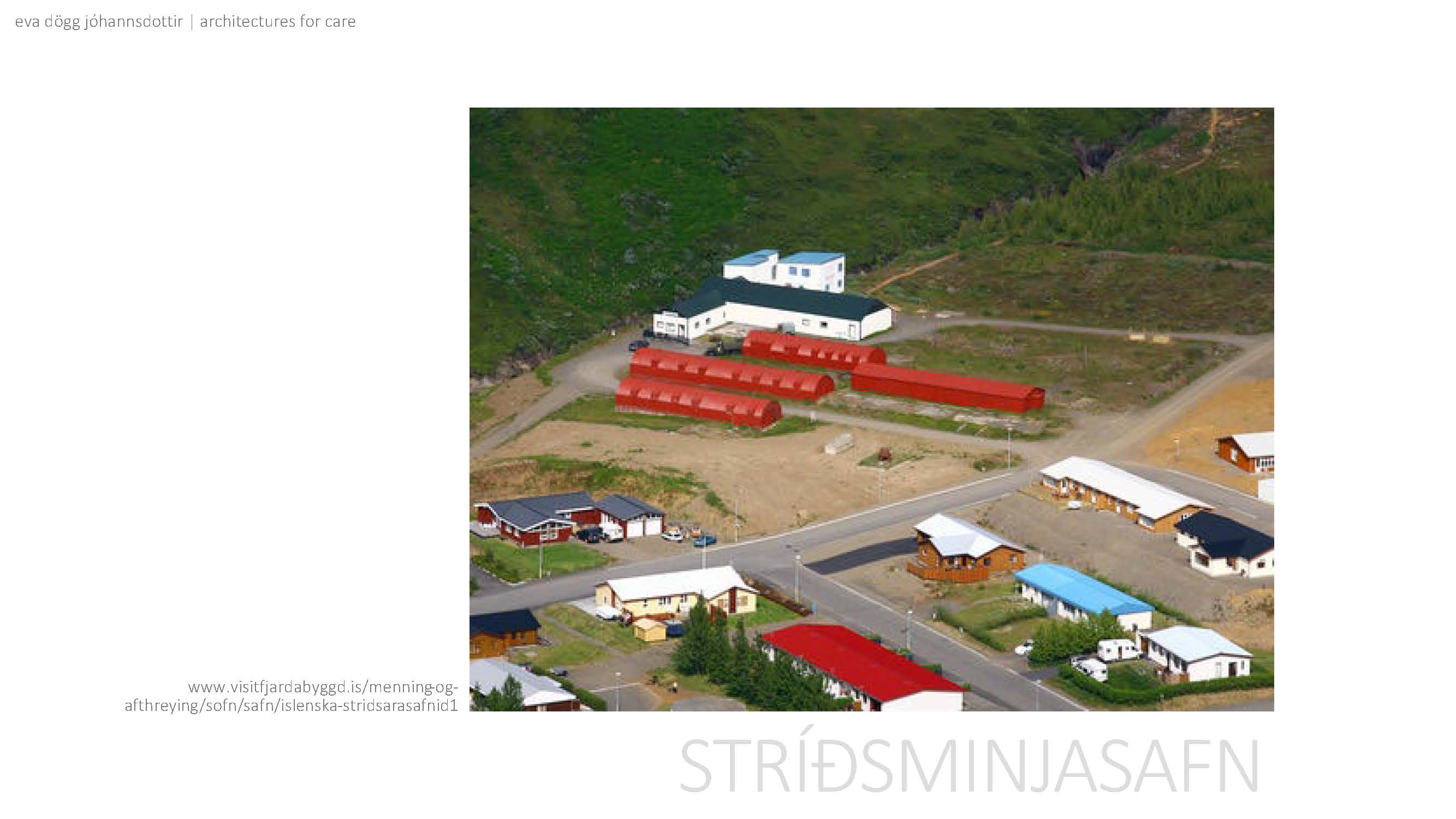

During the second World War, Reyðarfjörður was the base for a military hospital. The red military barracks seen in the image are only a remnant of the former base, which spanned over the majority of the town. Today, the structures are utilized as a war time museum.

As with many seaside villages in Iceland, Reyðarfjörður is known as a fishing village, more specifically for herring. It had a booming fishing industry and a population boom during its fishing era. Now I can’t remember if the fish left or if the fishing quota was sold, but the remnants of the fishing industry can be seen above. The fish processing facility (known as a frystihús in Icelandic) stands more or less abandoned in the middle of the town. The structure is underutilized and doesn’t add to the urban landscape.

I was part of the latest population boom. Thanks to the vast amount of space and possibility of clean and cheap energy, this location was seen as ideal for an aluminium factory. In the foreground of the image, you can see the factory itself and, in the background, further inside the fjord you can see the town of Reyðarfjörður. This aluminium smelter was the first one built by Alcoa in some 20 years. Most of its other smelters where past their prime, with the prime lifespan of an aluminium smelter being about 50 years.

I was eleven when my father relayed this information and I remember thinking to myself, what if I still live here in 50 years? I will be 61 years old, in this small remote village and next door we will have the remains of this giant factory.

Reyðarfjörður is a town that has had to deal with its main industry leaving. They were able to utilize some of the structures from WWII to create a museum. The fish processing facility stands unused and as far as I know, the community is not working towards utilizing the building left behind. How will the town then deal with the massive industrial structure of an aluminium plant?

At this point you might ask, Eva, where are you going with this? The group project was based in Reykjanes and the title of your project is Frystihúsið in Vogar. I say, patience, we will get there in time.

Most towns in Iceland are not at present dealing with the issue of what to do with an industrial structure the size of an aluminium smelter. Many towns have a similar history as Reyðarfjörður though, in that the main income came from fishing. For some places the fish simply left, or the quota to fish was sold someplace else, or either the health and safety regulations or the technology for processing had evolved to the degree that the old fish processing facilities didn’t meet needs going forward.

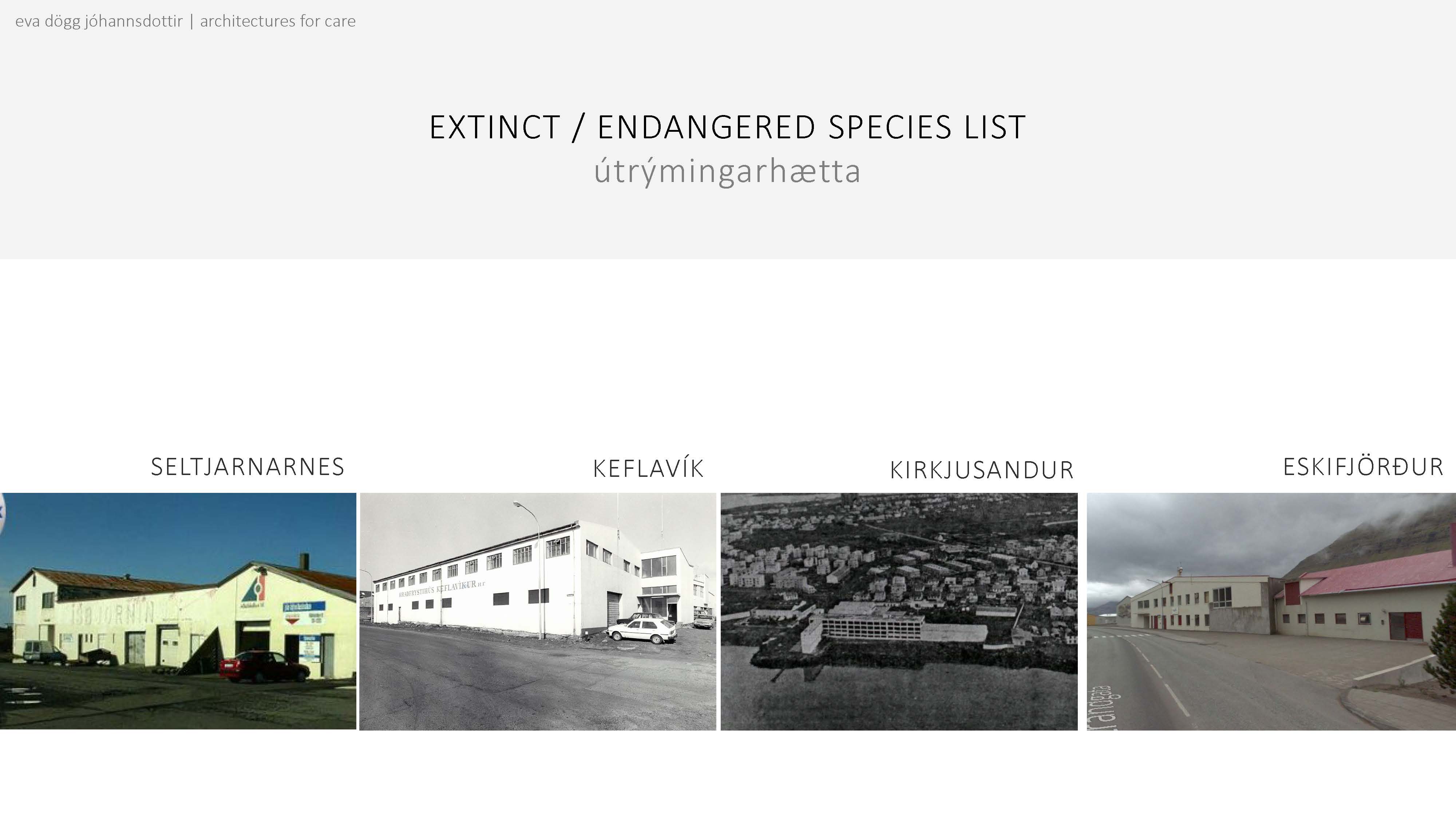

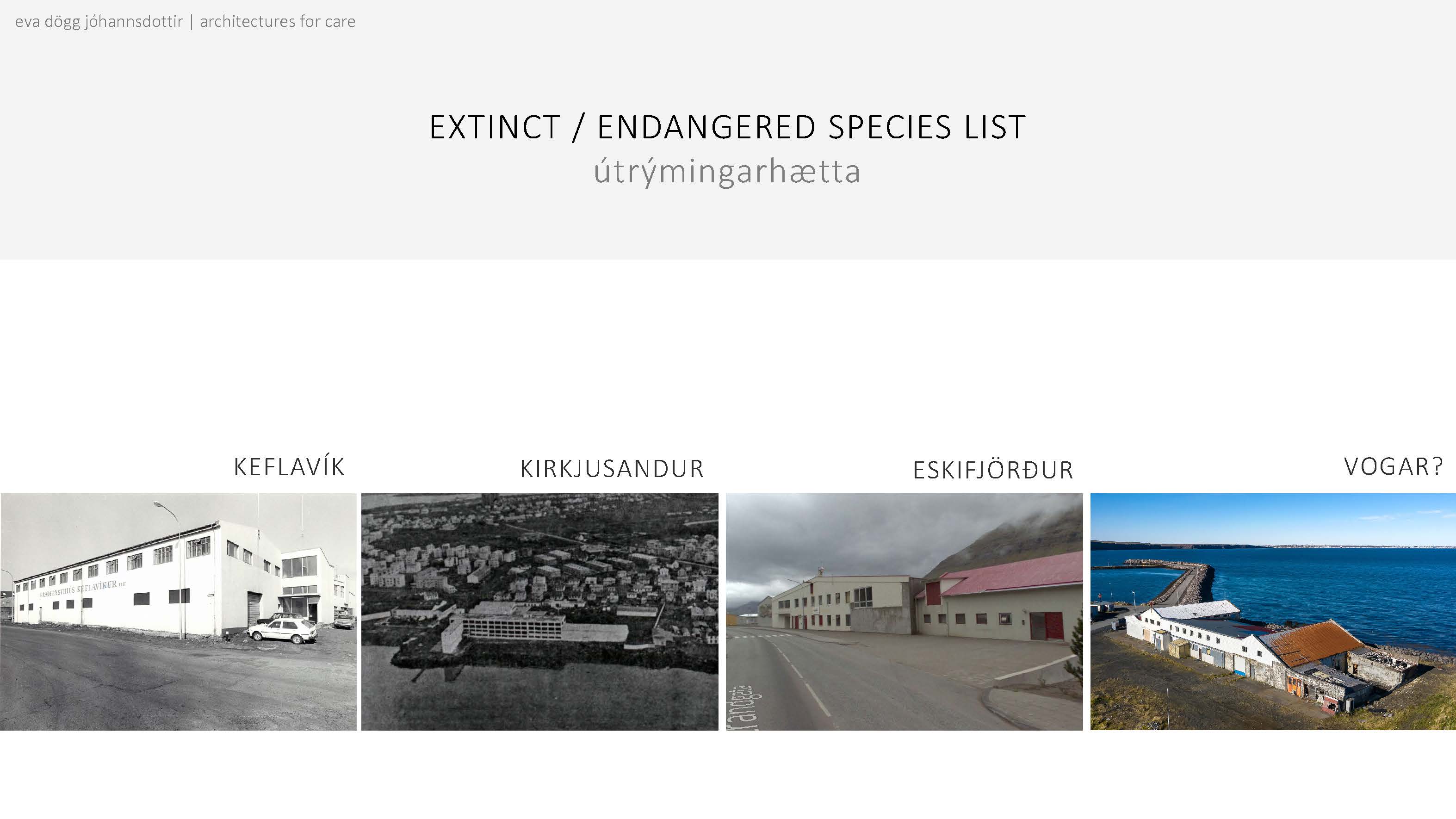

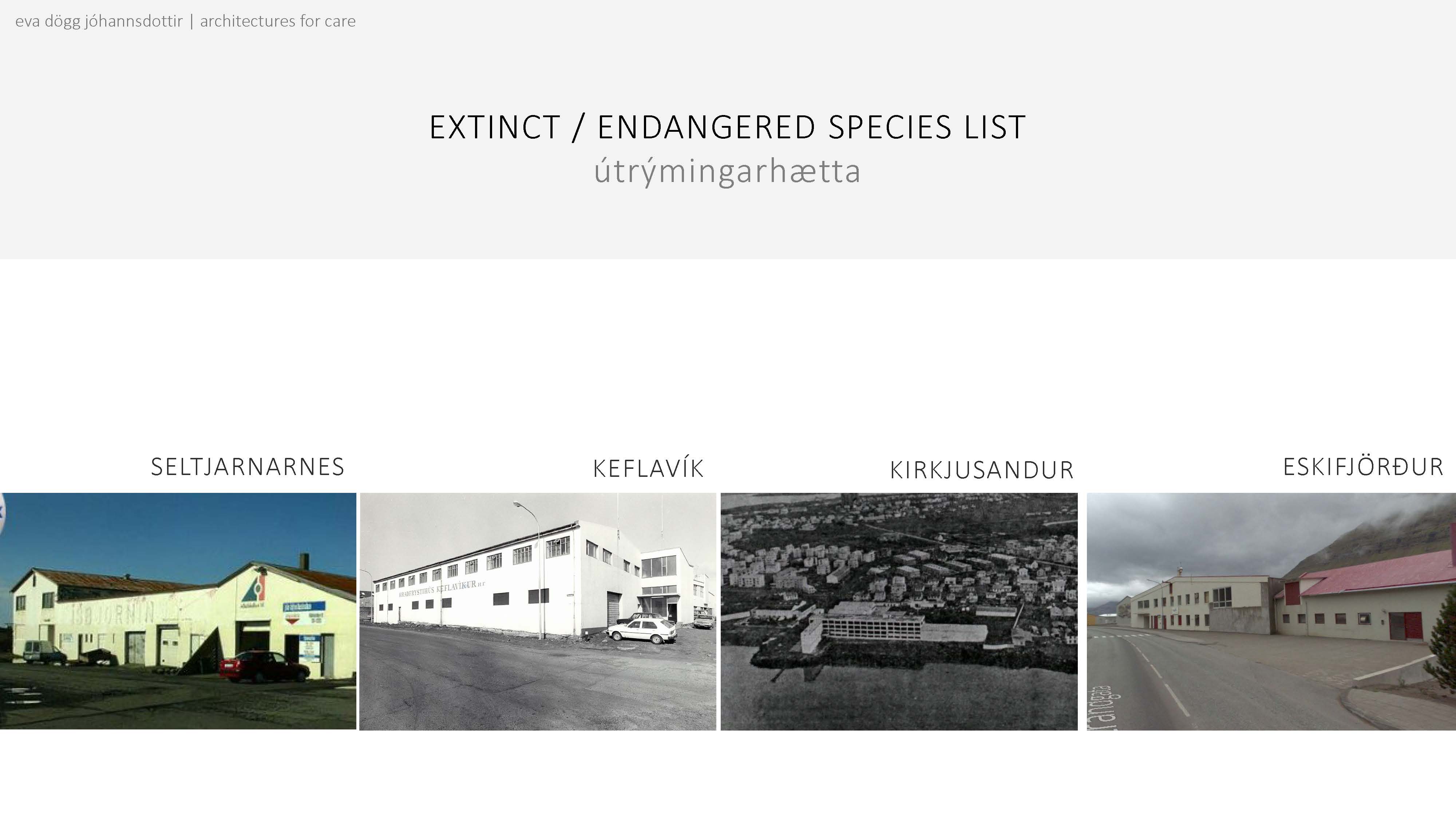

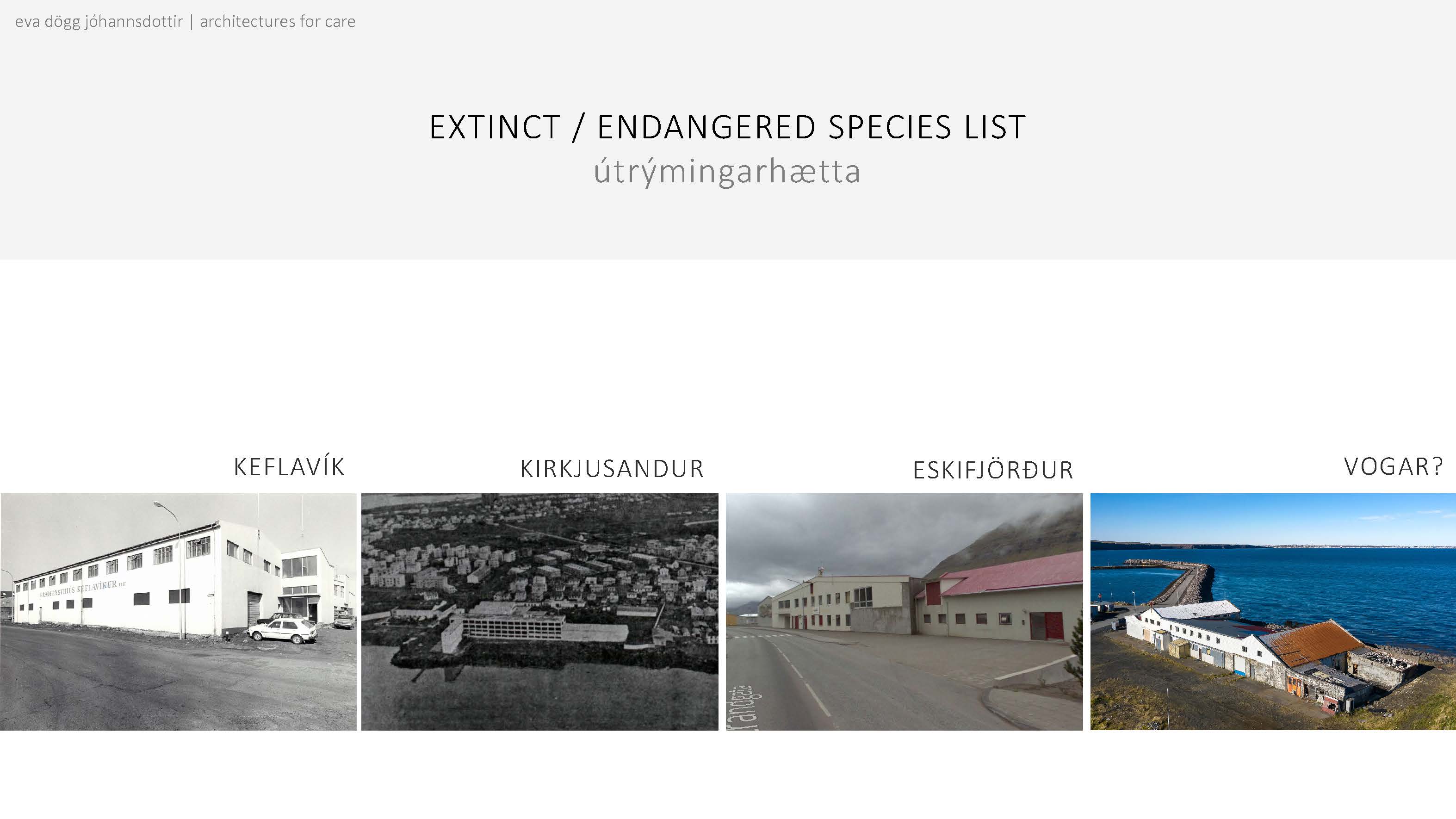

So now these townships all over Iceland are grappling with what should be done with these structures. I have compiled an extinct/endangered species list of these fish processing facilities. The list is far from exhaustive.

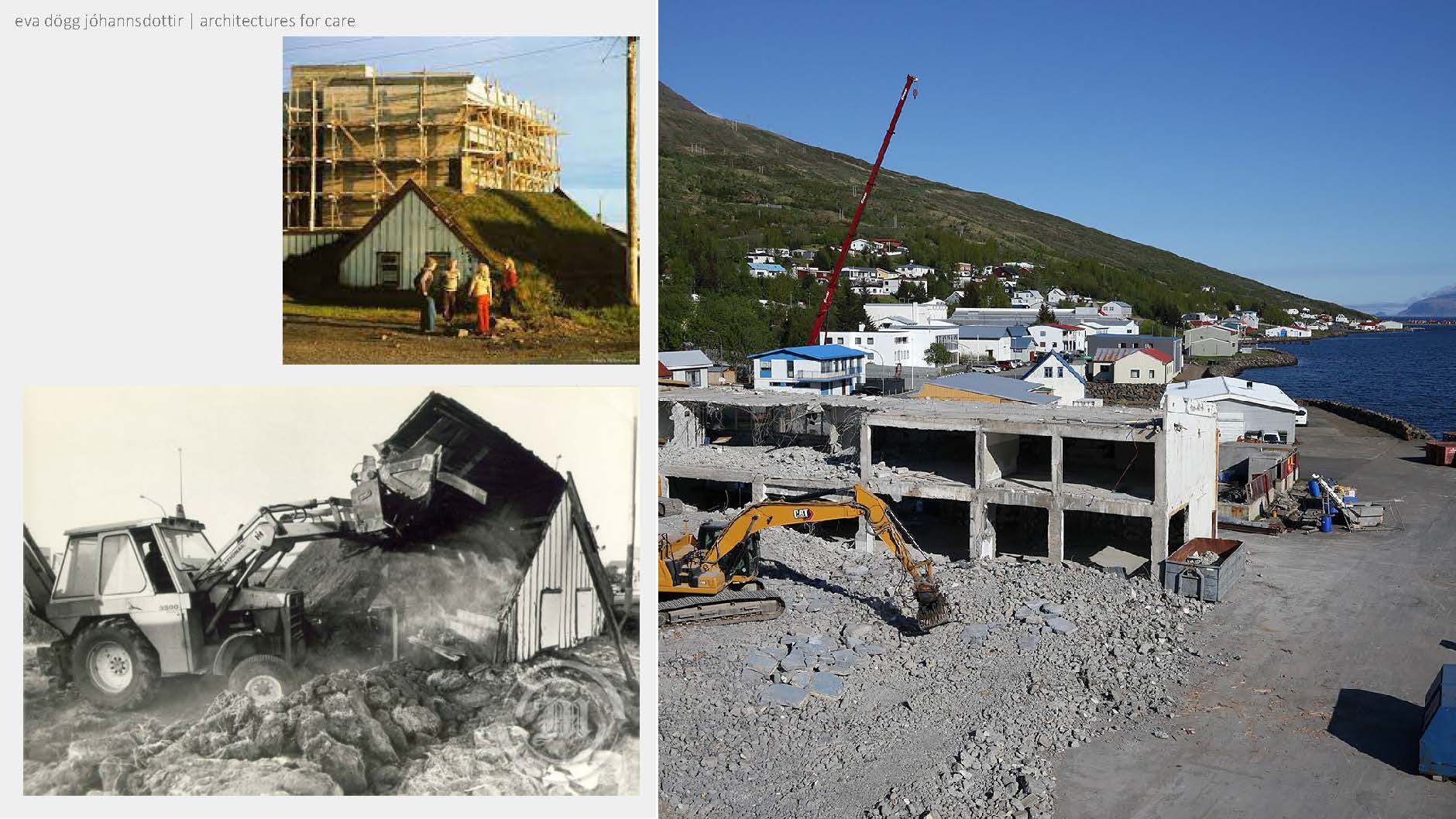

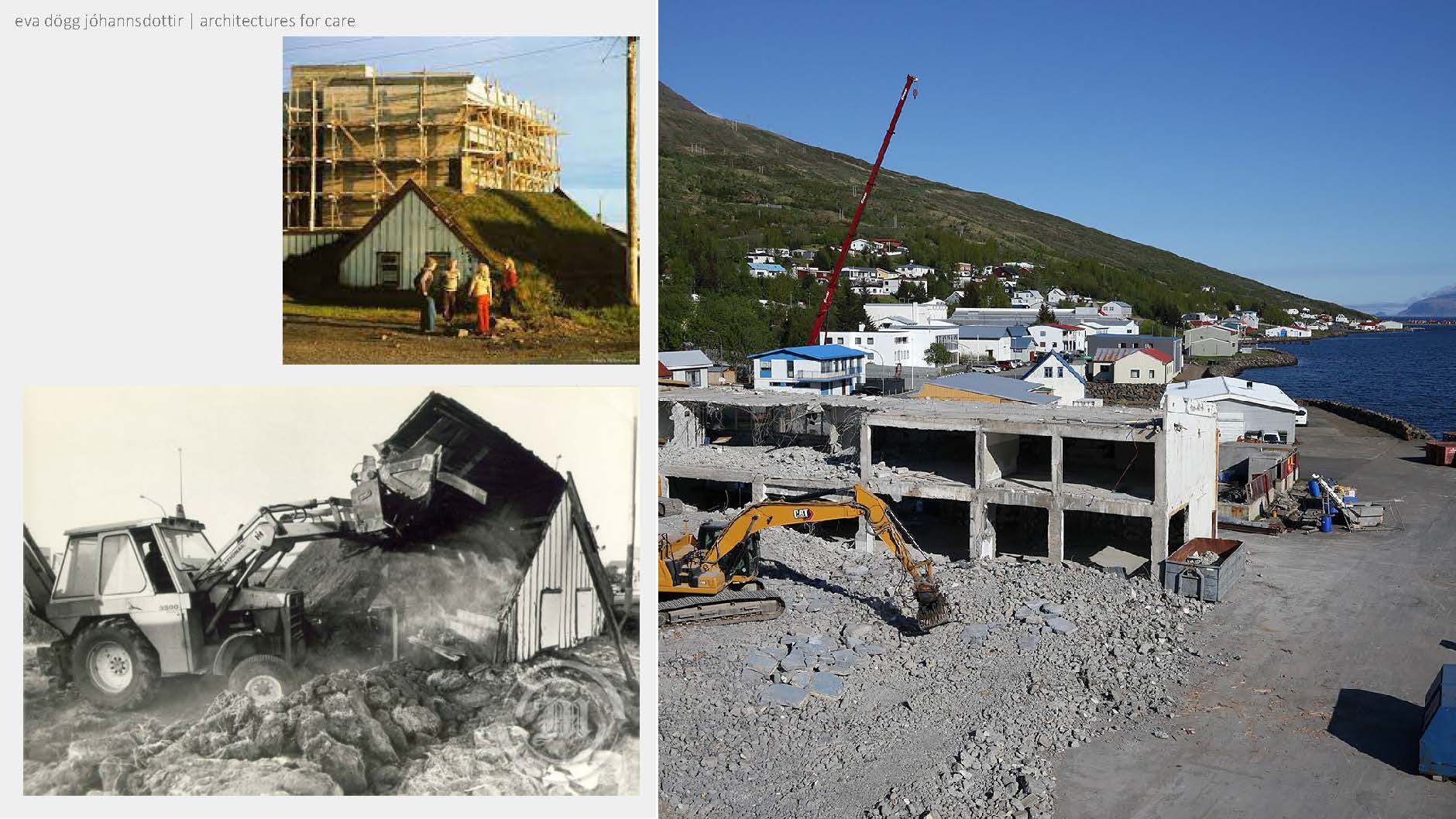

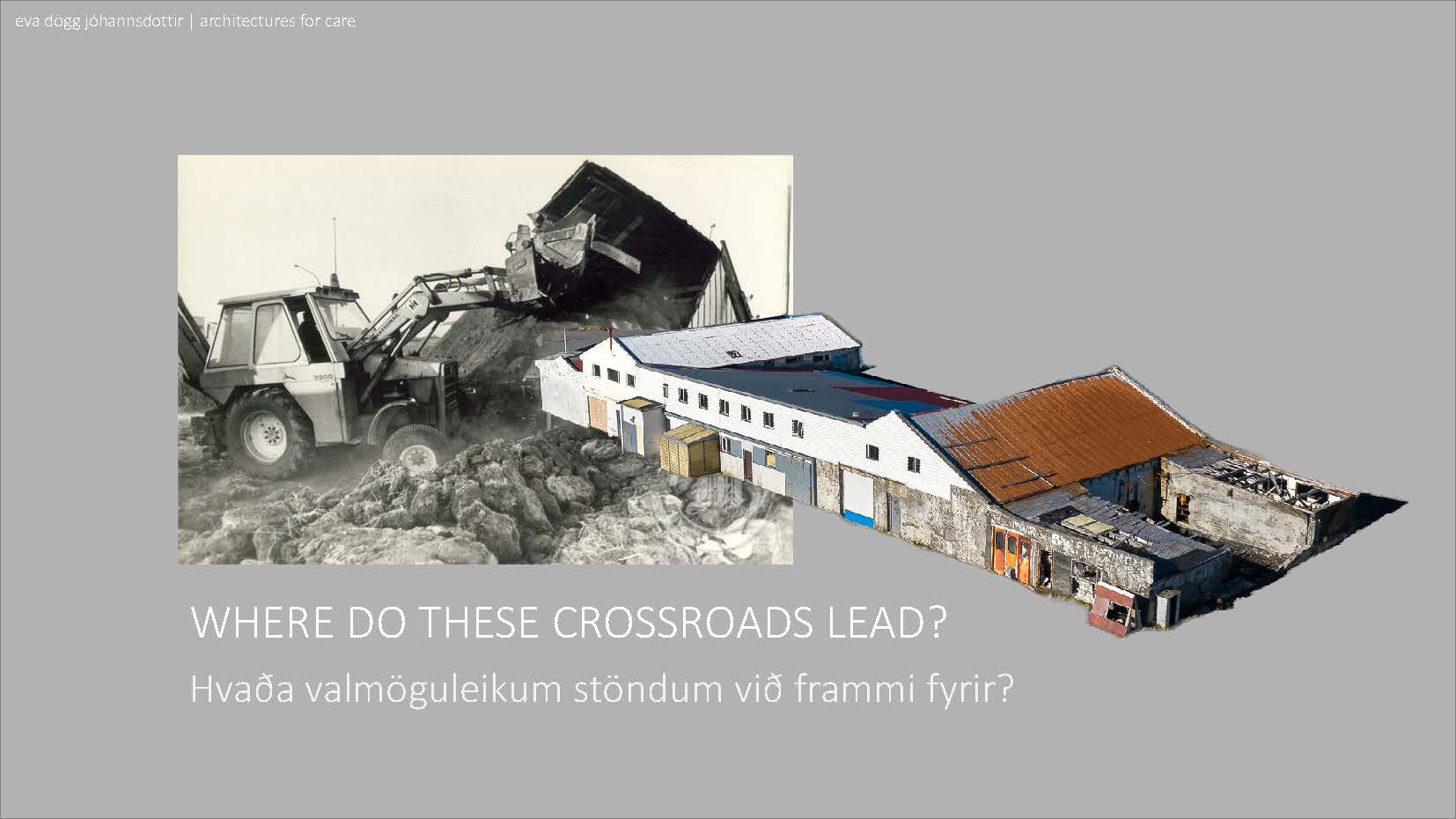

The newest example of a building moving from the endangered to the extinct list, was located in Eskifjörður, coincidentally, the town closest to Reyðarfjörður. The area in front of the building (as seen on the left) is supposed to become the towns downtown or centre area. Many of these fishing villages don’t have an obvious centre so recently a lot of towns have started planning for one. Eskifjörður deemed the fish processing building not fit for their idea of a new town centre, so it was demolished this summer (2022). Although I don’t know the finer details of its structural integrity, I will give myself that it was most likely salvageable. The structure was concrete, meaning that a vast amount of carbon has already been emitted for its creation. The most environmentally friendly idea would have been to use the building and adapt it to a new purpose. Keeping the building would have also created a layer of history for the new centre.

This mentality reminds me of how we dealt with the turfhouse. There was an essence of shame and feelings of dirtiness associated with them. The populace was glad to be rid of them, of reminders of the reality of living in a turfhouse. The last turfhouse in Reykjavík (seen on the left) was demolished in 1980. This begs the question of when the last fish processing building will be demolished. What are we leaving behind for the next generation?

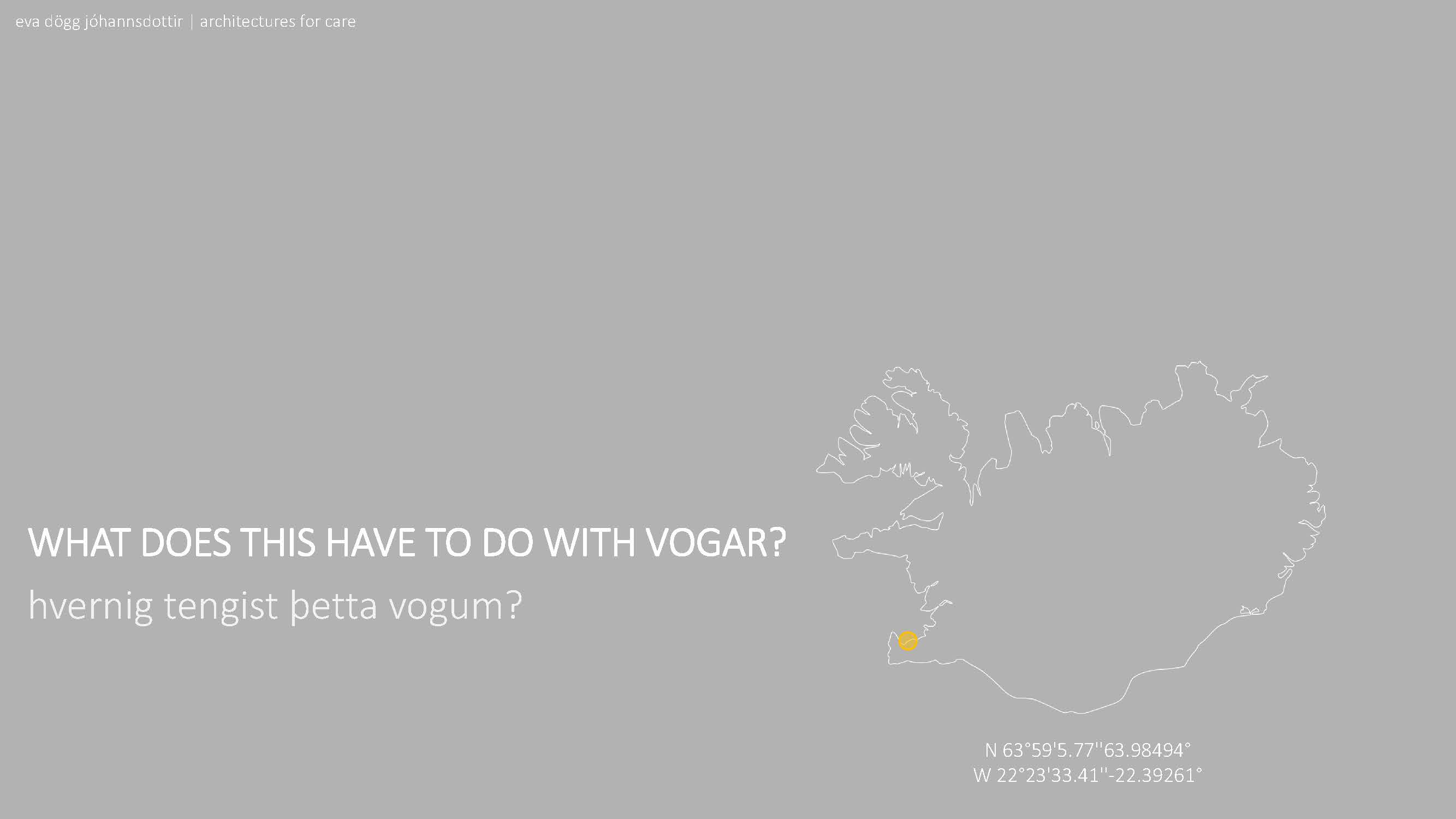

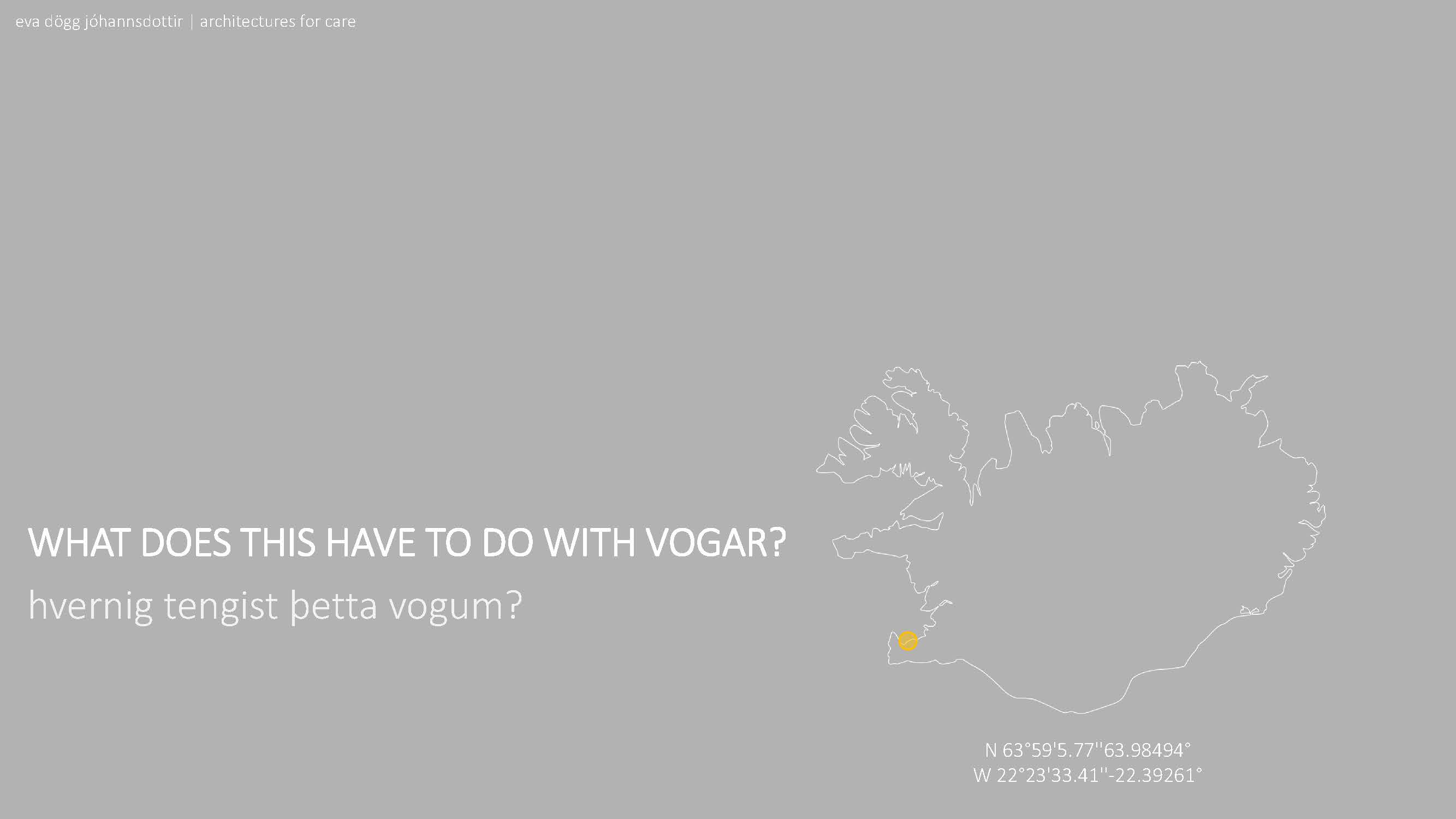

What does the demolition of a fish processing facility in Eskifjörður have to do with Vogar? I am glad you asked!

The large yellow dot above highlights the fish processing facility in Vogar. The small yellow dot shows us where Vogar is in Iceland.

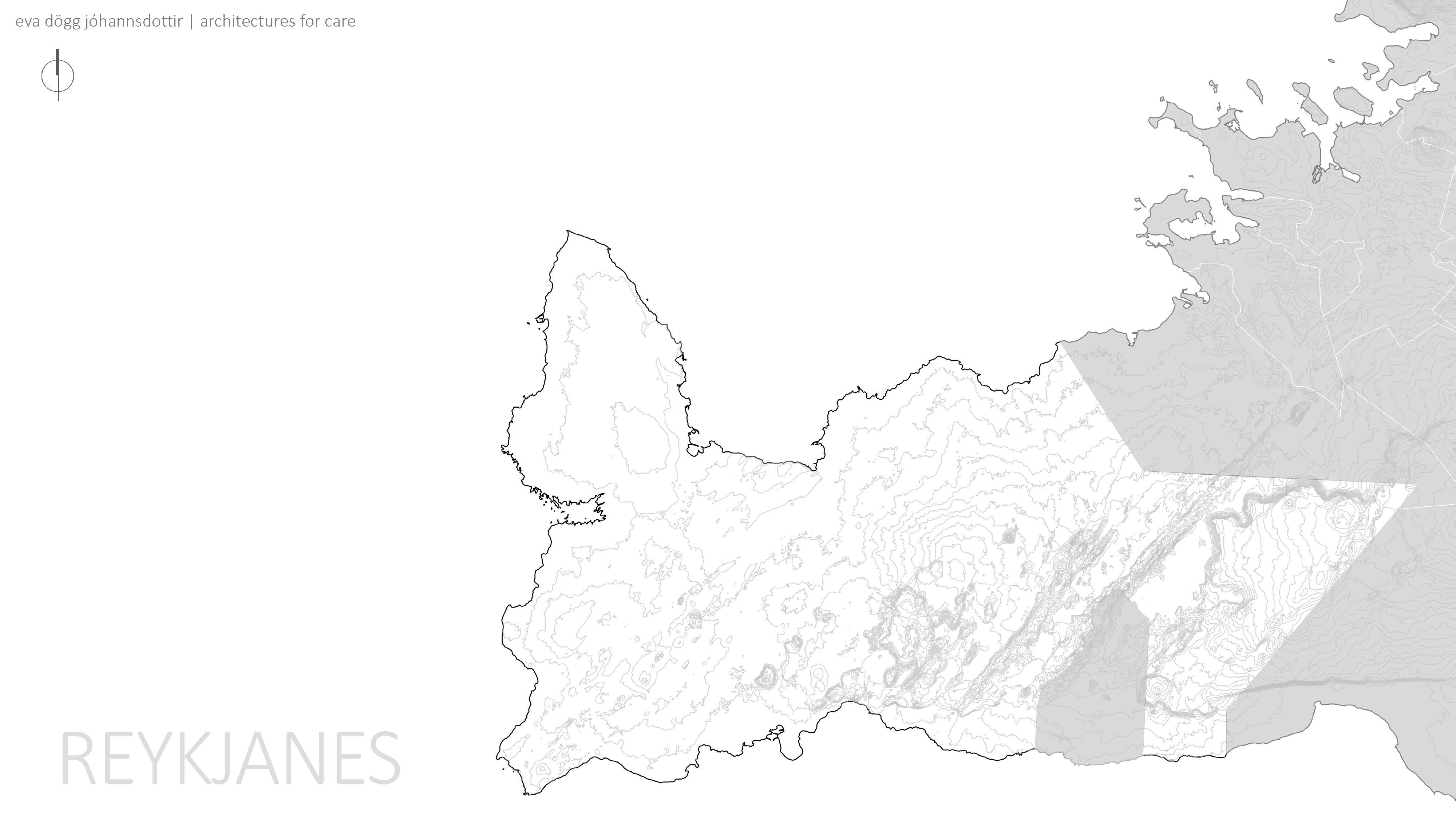

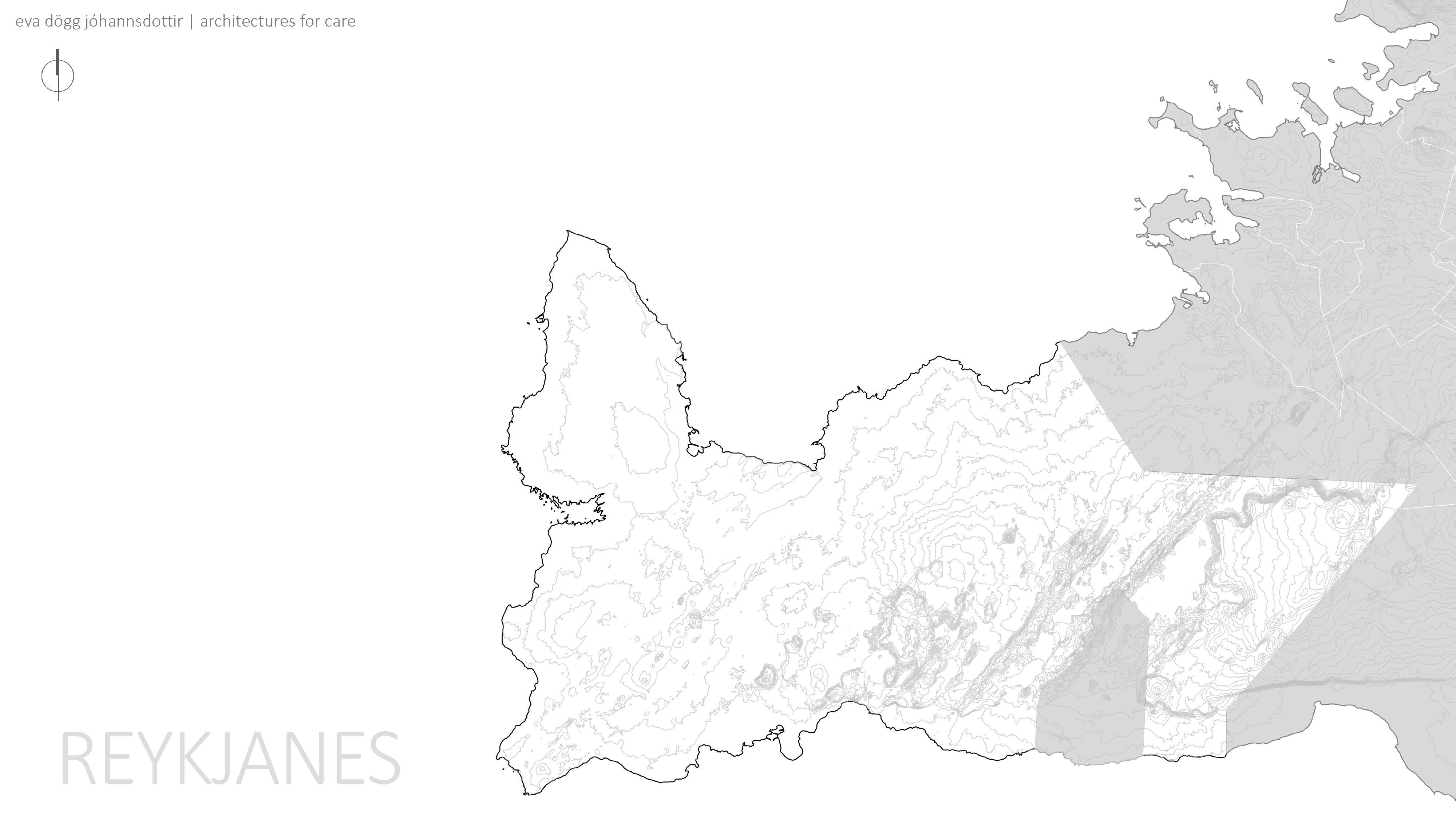

If we zoom in to the southwest coast, we see Reykjanes.

In Reykjaness we have the municipality and town of Vogar.

If we very

quickly look at our extinct/endangered species list...

If we very

quickly look at our extinct/endangered species list... We must regrettably

add the fish processing facility (Frystihús) in Vogar to the list.

We must regrettably

add the fish processing facility (Frystihús) in Vogar to the list.  The town of

Vogar has plans to develop the land which the fish processing facility stands

on. Originally the building was set to be demolished. Vogar has an active group

named Sögufélagið (e. the history association) which felt that the building was

too significant to the town to be bulldozed. They contacted Minjastofnun

(e. The Cultural Heritage Agency of Iceland) to look at the building.

Under normal circumstances this building would have never landed on the desk of

Minjastofnun. Iceland has a 100-year rule, where houses built more than a

hundred years ago automatically fall under the jurisdiction of Minjastofnun.

Other buildings which are seen extremely culturally significant or the clearest

example of a style of architecture might also fall under their protection. This

facility was built in 1942 and is a very typical fish processing facility, if

in slightly bad shape. After a meeting with town officials, it seems that the

town itself is now more open to plans which utilize part of the building or at

least reference the history of the area in some shape or form.

The town of

Vogar has plans to develop the land which the fish processing facility stands

on. Originally the building was set to be demolished. Vogar has an active group

named Sögufélagið (e. the history association) which felt that the building was

too significant to the town to be bulldozed. They contacted Minjastofnun

(e. The Cultural Heritage Agency of Iceland) to look at the building.

Under normal circumstances this building would have never landed on the desk of

Minjastofnun. Iceland has a 100-year rule, where houses built more than a

hundred years ago automatically fall under the jurisdiction of Minjastofnun.

Other buildings which are seen extremely culturally significant or the clearest

example of a style of architecture might also fall under their protection. This

facility was built in 1942 and is a very typical fish processing facility, if

in slightly bad shape. After a meeting with town officials, it seems that the

town itself is now more open to plans which utilize part of the building or at

least reference the history of the area in some shape or form.

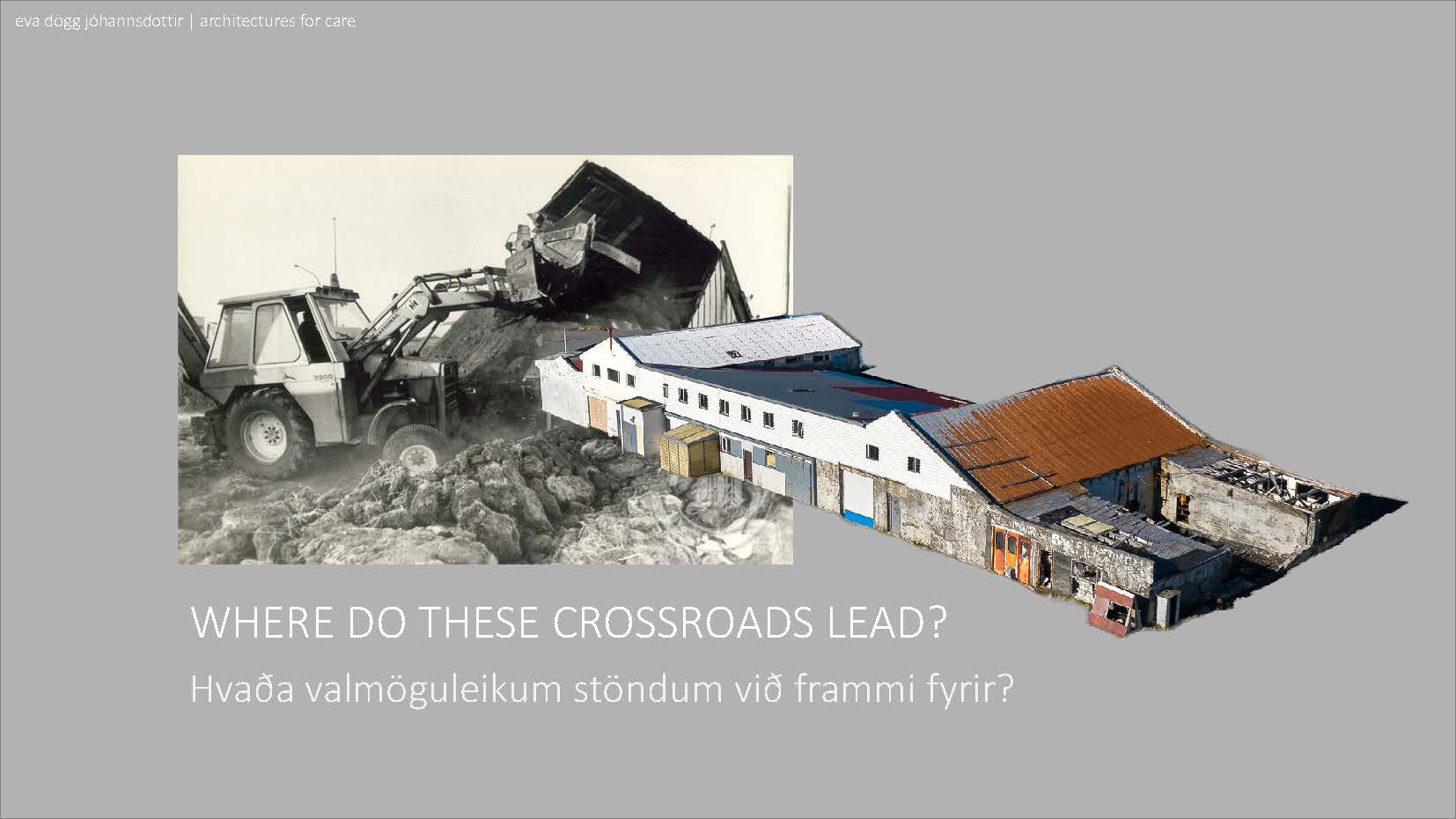

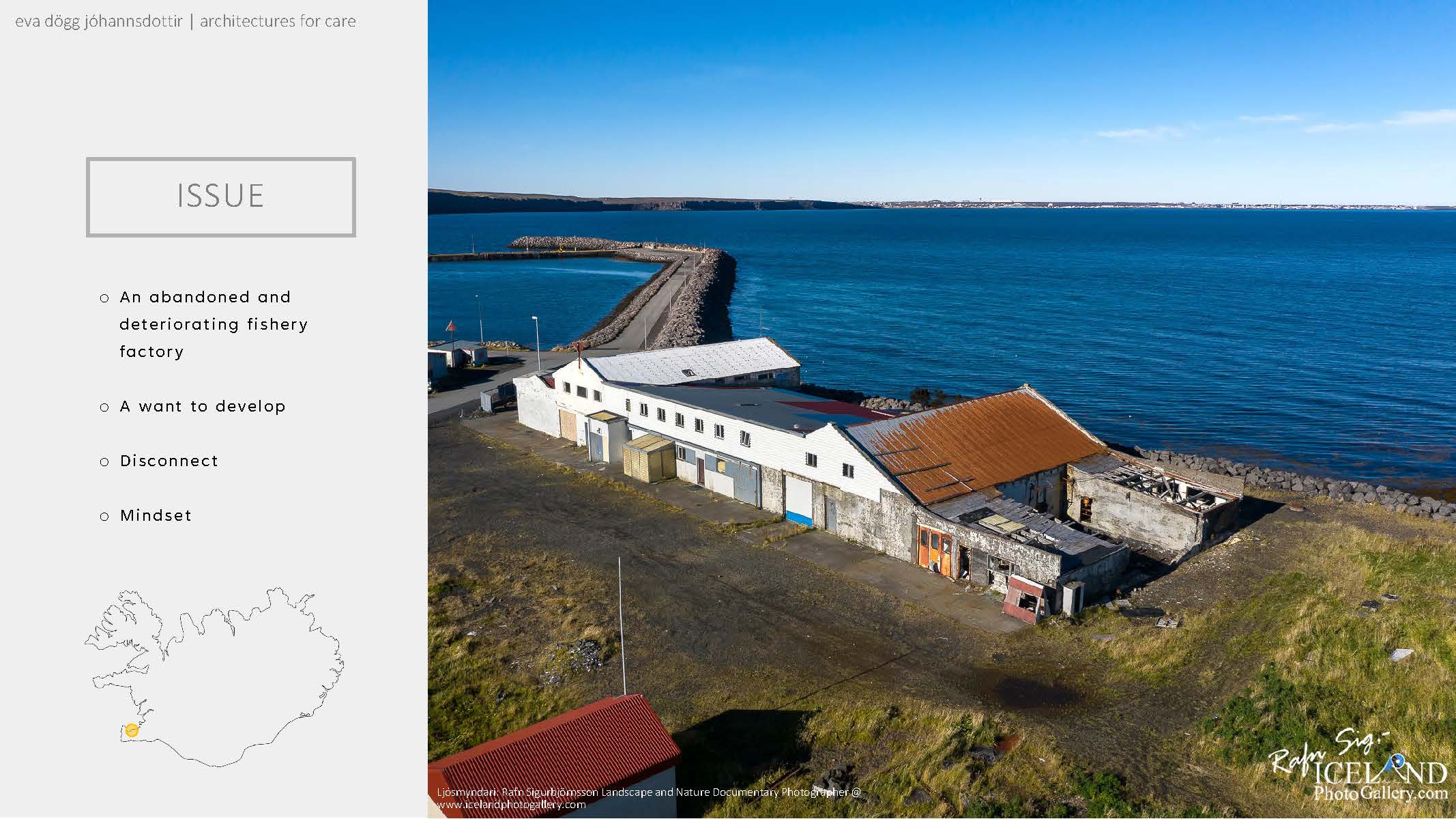

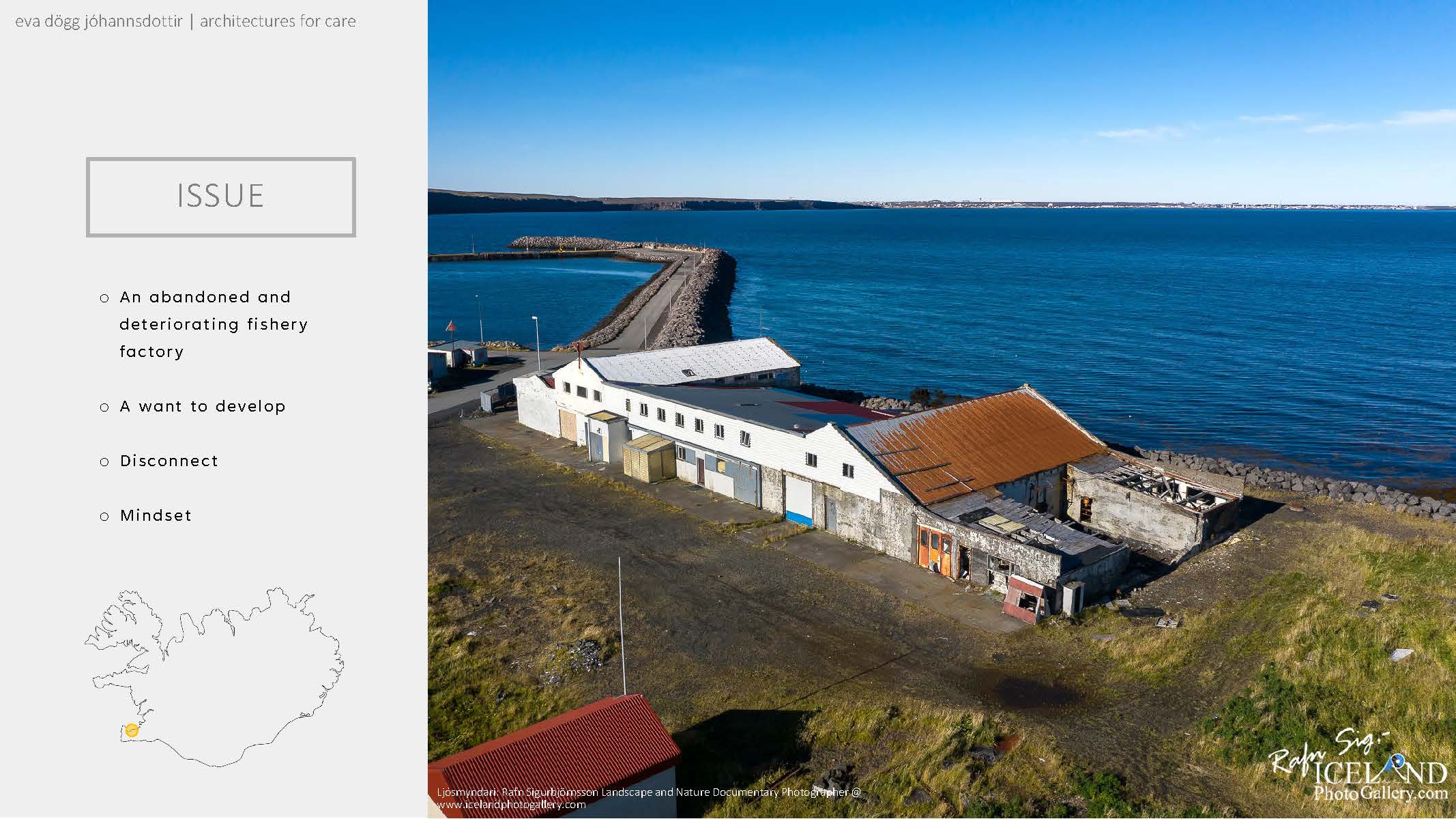

To summarize:

There is an old and deteriorating fish processing facility. The town wants to develop but there is a disconnect between what the town leadership wants and what, at least some, inhabitants would like to see. The mindset that Icelandic people generally have towards these buildings is also worrisome and could lead to irreversible decision making, impacting future generations and their connection to the heritage of the place.

Vogar, along with other fishing villages, now stand at a crossroad. The question is, what decision will they make?

Keeping the structure and working around it has the possibility of upholding three of the UN’s sustainability goals.

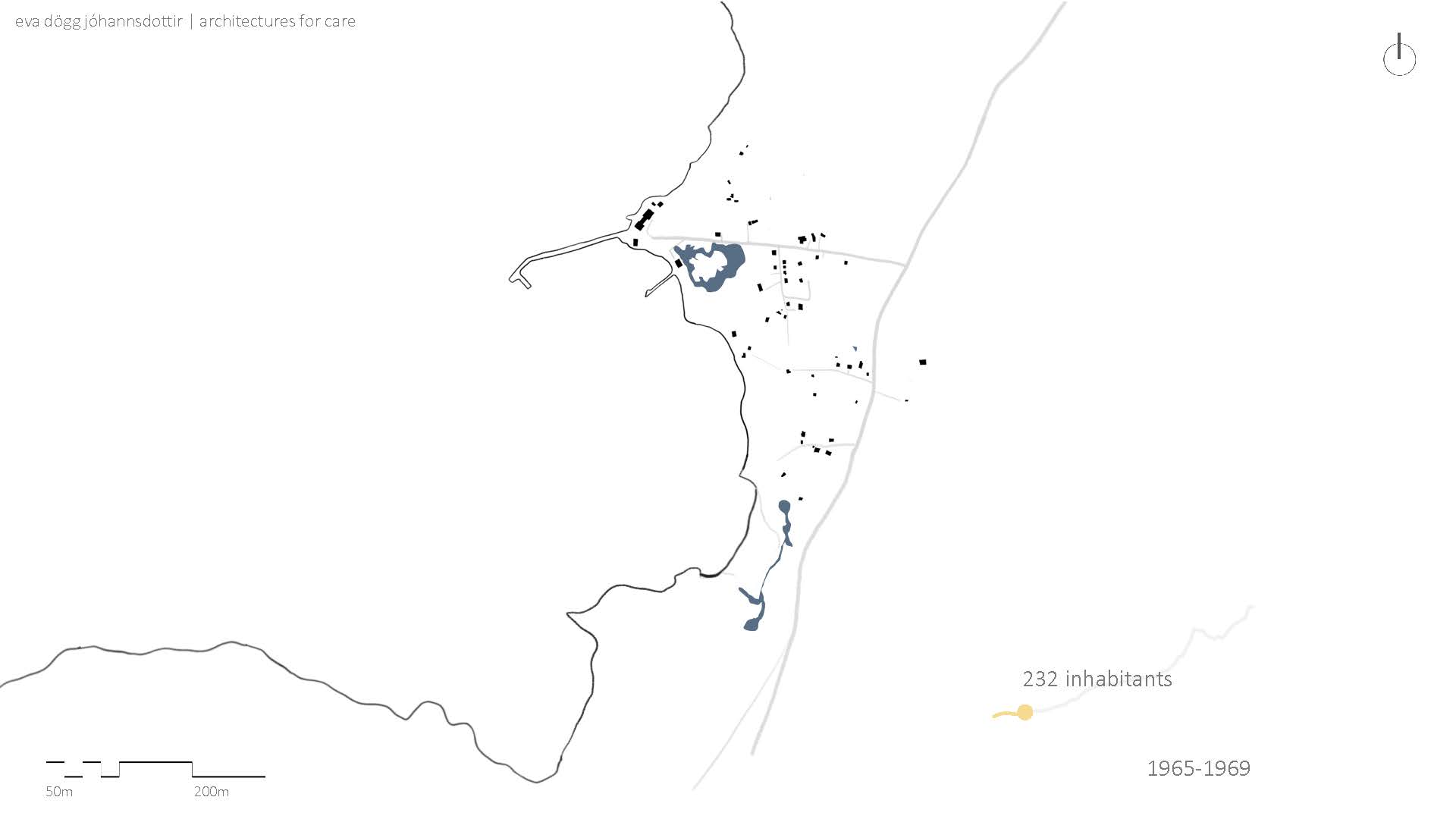

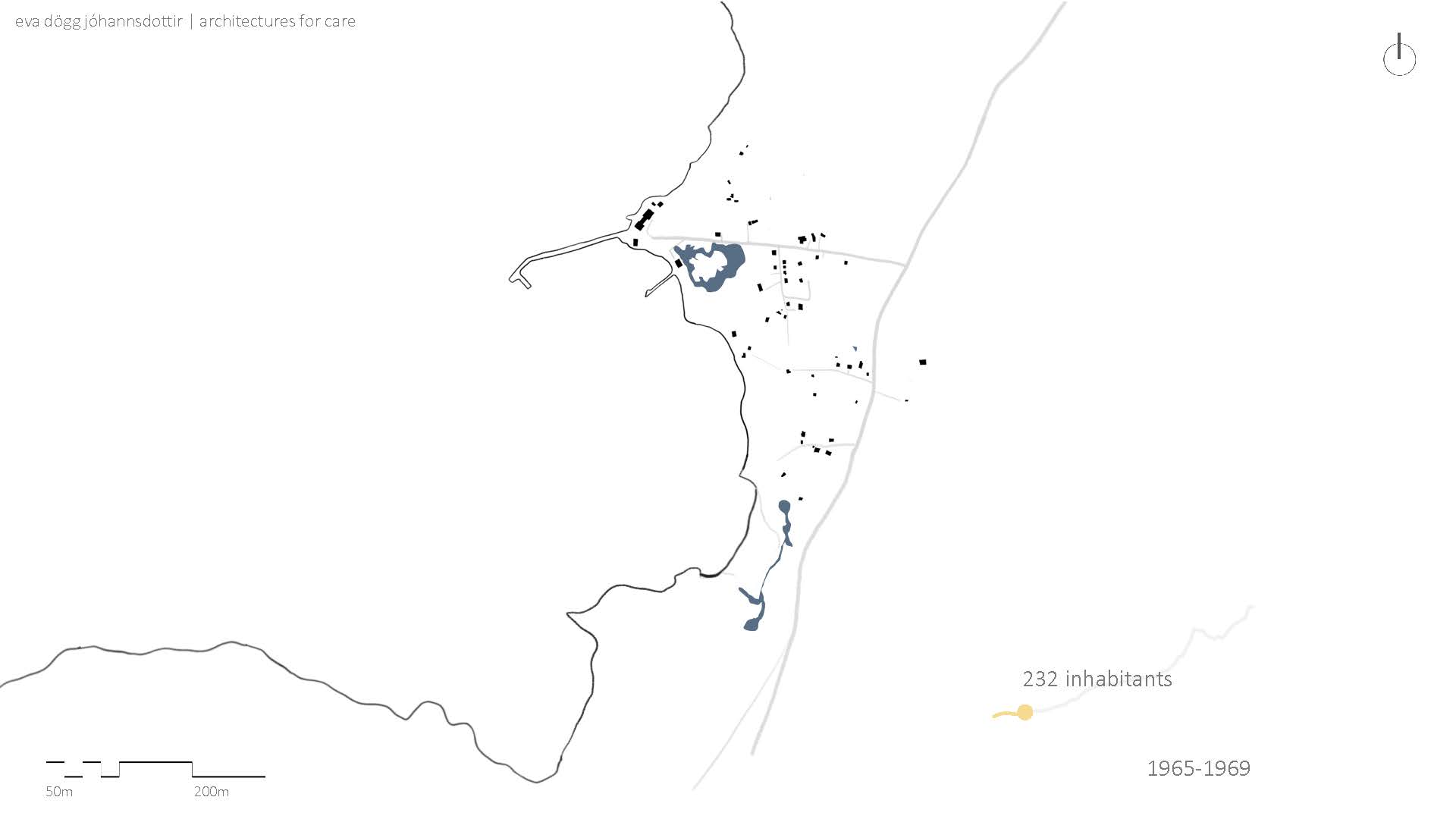

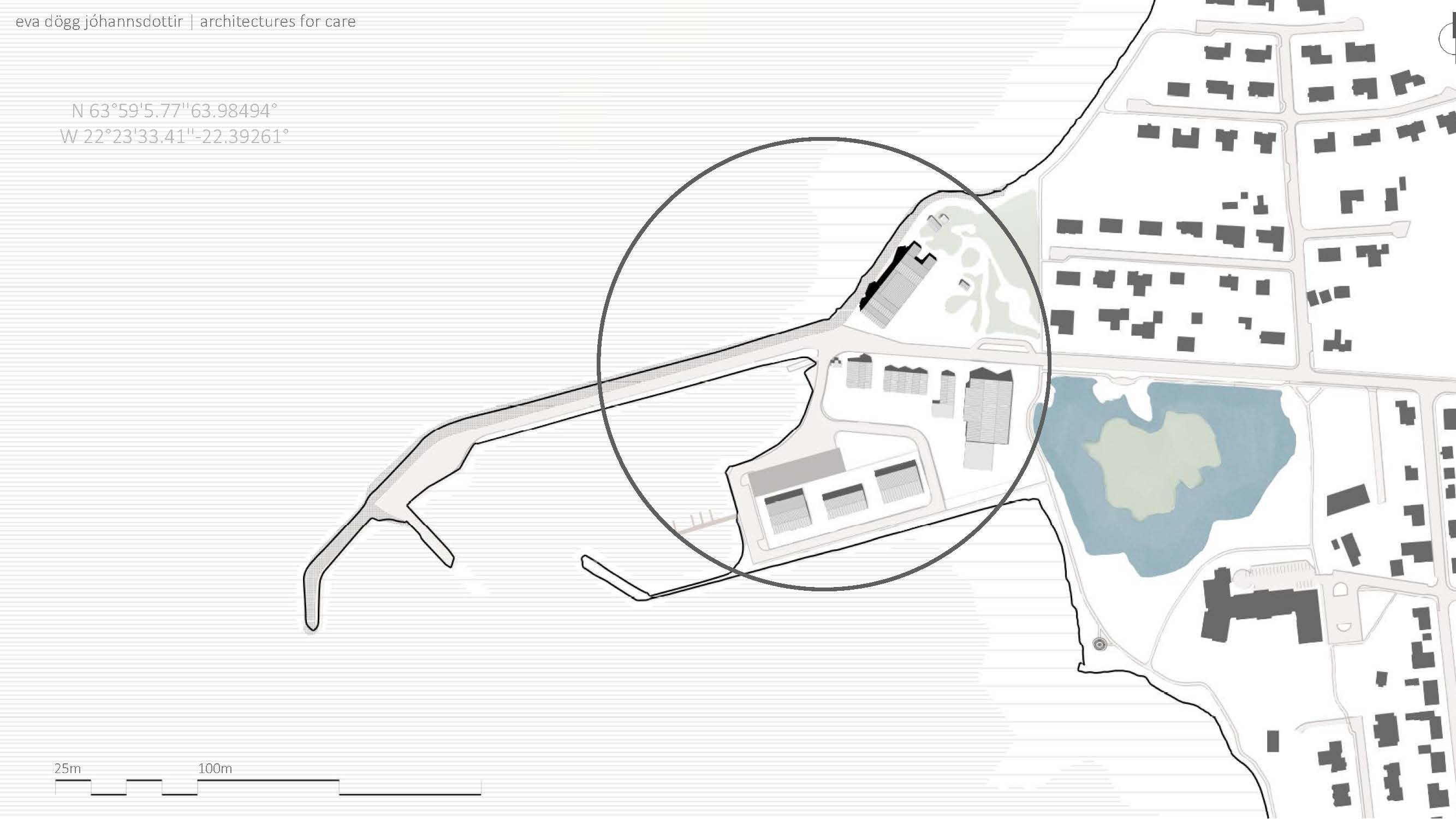

Within the town of Vogar we can see where the frystihús is (the yellow dot). The blue on the map shows water. Just southeast of the frystihús you can see the town’s pond, with a small island in it (which is not really an island but very tall and dense grass). The green shows green areas within the town.

The plot of land which the building stands on is large, which would allow for a lot of additional mass to be added around the frystihús. This would also allow for a fair bit of flexibility and creativity in mass placements.

Going further, it might even be a good idea to look at the entire harbour area as a whole. Reworking the entire context of both the harbour and the frystihús could be mutually beneficial.

[slideshow]

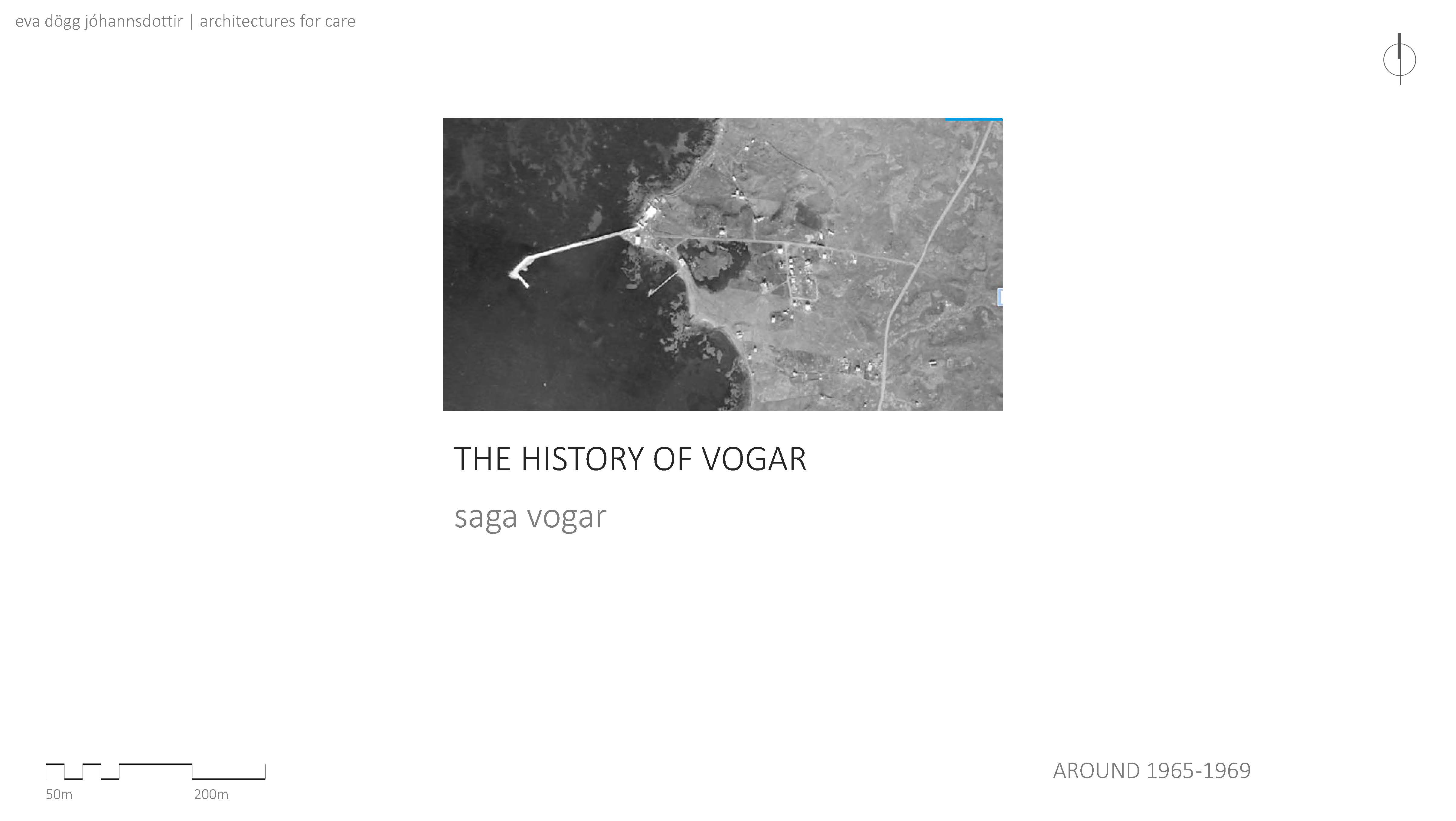

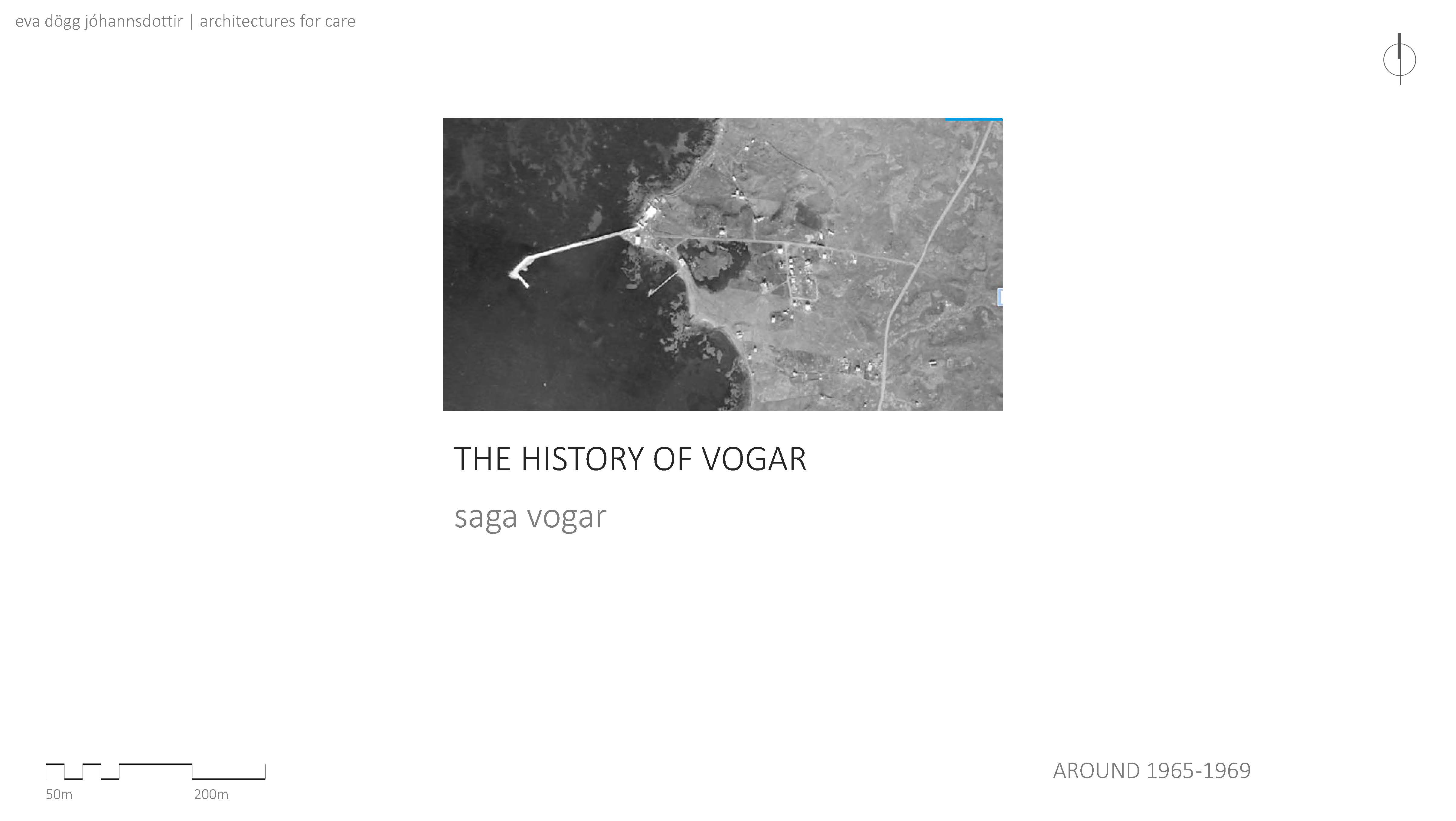

Going through the urban history of Vogar, one can see that the frystihús is the heart, or foundation of the town. The plans are traced from aerial photographs. The first aerial photograph wasn’t dated but simply tagged as “eldri” or older. Using a diagram of the growth of the frystihús itself, the image can be dated within a five-year span. After the first map we have a 40 year time jump followed by maps with intervals of three years.

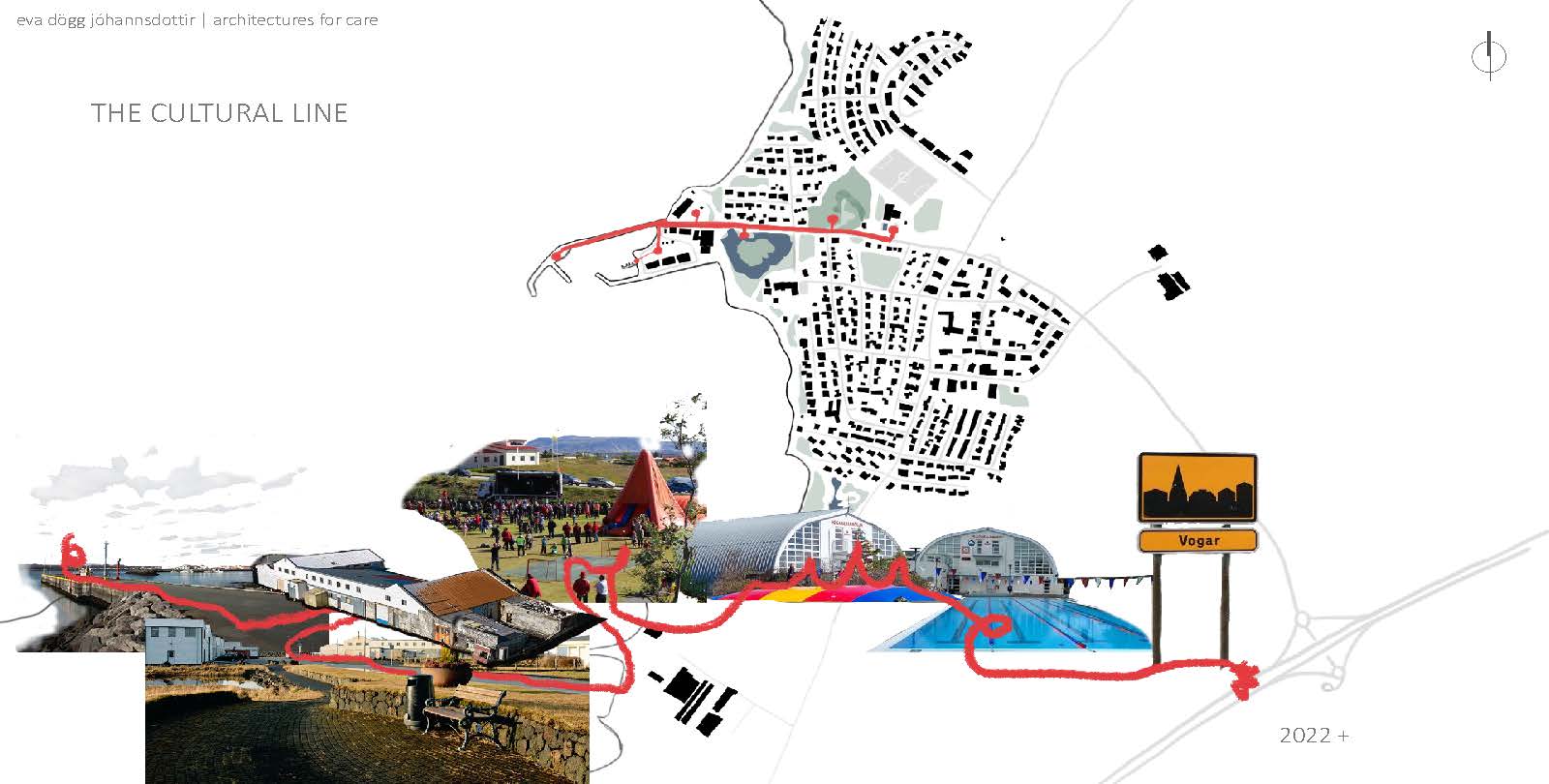

Vogar

has a preschool, a grade school (ages 6-16), apartments for the elderly and a

municipal council office. [red]

Vogar

has a preschool, a grade school (ages 6-16), apartments for the elderly and a

municipal council office. [red] They have two types of accommodations, a motel, and a camping site. [green]

For recreation Vogar has a swimming pool and indoor sports facility. Adjoined to the sports facility is after school care and a children’s community centre. Behind the sports facility they have a full-sized soccer field. They also have a small park with a frisbee golf course where they hold an annual town festival. [yellow]

Vogar’s festival, Fjölskyldudagar (e. family days) is held mid-august. The town is split into four neighbourhoods and each neighbourhood is then decorated with their given colour. The town has a packed agenda for the festival with a wide variety of activities around town. The park, which is fairly sheltered by a hill on one side and a barrier of trees on the other, is set up with a stage where a concert is held on the last night. After the concert, gatherings and parties are held in each neighbourhood, with someone’s home becoming a melting pot of all ages, from teenagers to grandparents drinking and revelry into the night.

I let myself wonder how the neighbourhood division will change once the current development plans finish. If a new neighbourhood colour will be created or if the newest housing will be part of the yellow neighbourhood. As is the majority of Vogar’s residential housing is made up of single-family homes. The new development is largely made up of apartment buildings, which means that the area is denser with smaller homes. The culture of hosting parties for the entire neighbourhood might not be feasible with this evolution. In the grand scheme of things, having more diverse types of housing and a smaller footprint per person is positive. The possibility of smaller culture changes which it might affect are in essence negligible, but it will be interesting seeing how the community will adapt.

The hatched areas are where I can image the town will expand in the future. If this area where to be developed, the main road into the town would become even more central and balanced.

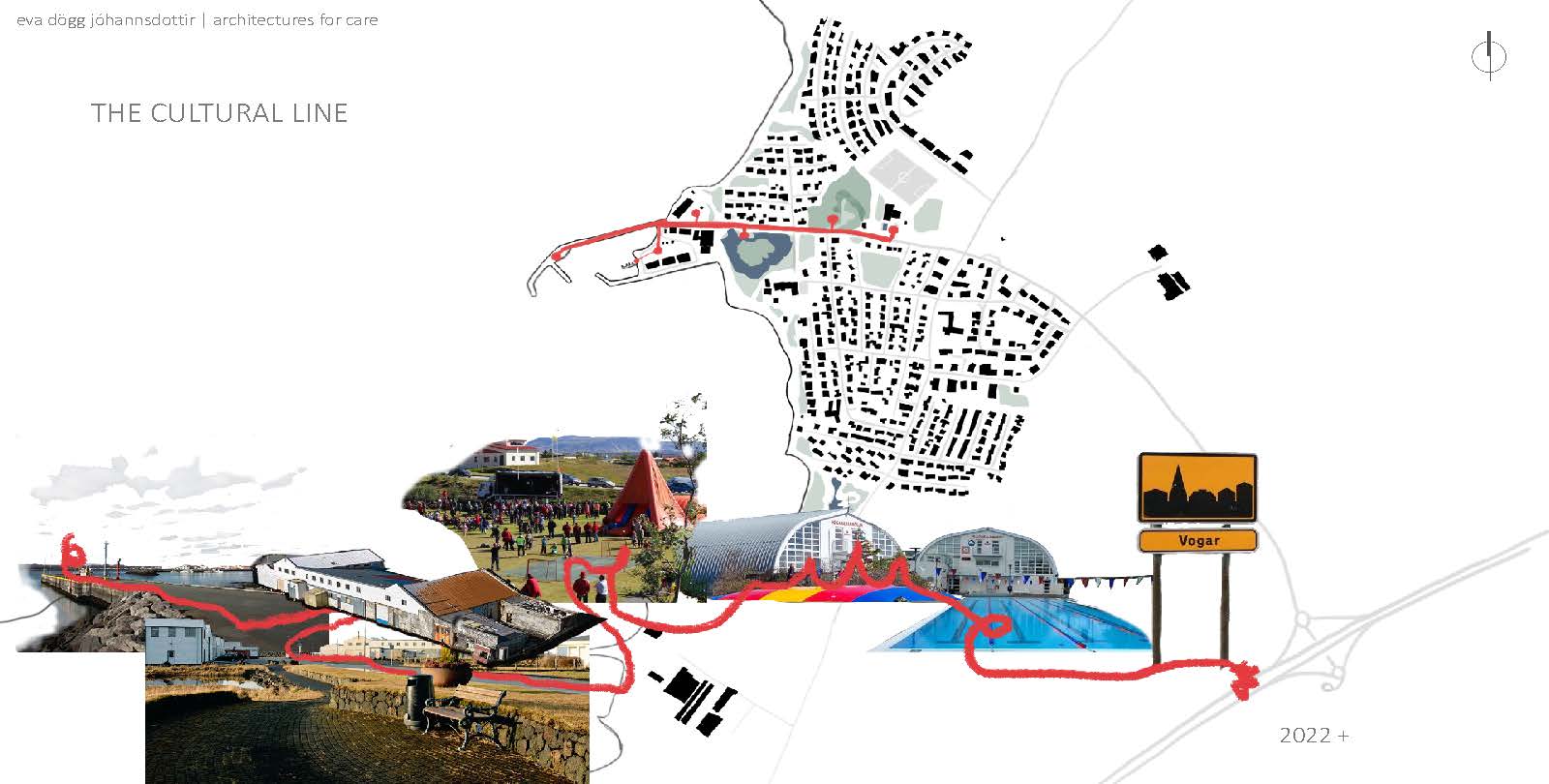

The hatched areas are where I can image the town will expand in the future. If this area where to be developed, the main road into the town would become even more central and balanced. What all this mapping and information gives us is the existence (or possible existence) of a cultural line which follows the end of the main road. It starts at the swimming pool and sports facility, leads to the park and the pond, followed by the harbour area.

What all this mapping and information gives us is the existence (or possible existence) of a cultural line which follows the end of the main road. It starts at the swimming pool and sports facility, leads to the park and the pond, followed by the harbour area.  A photocollage might give a better feel for the area.

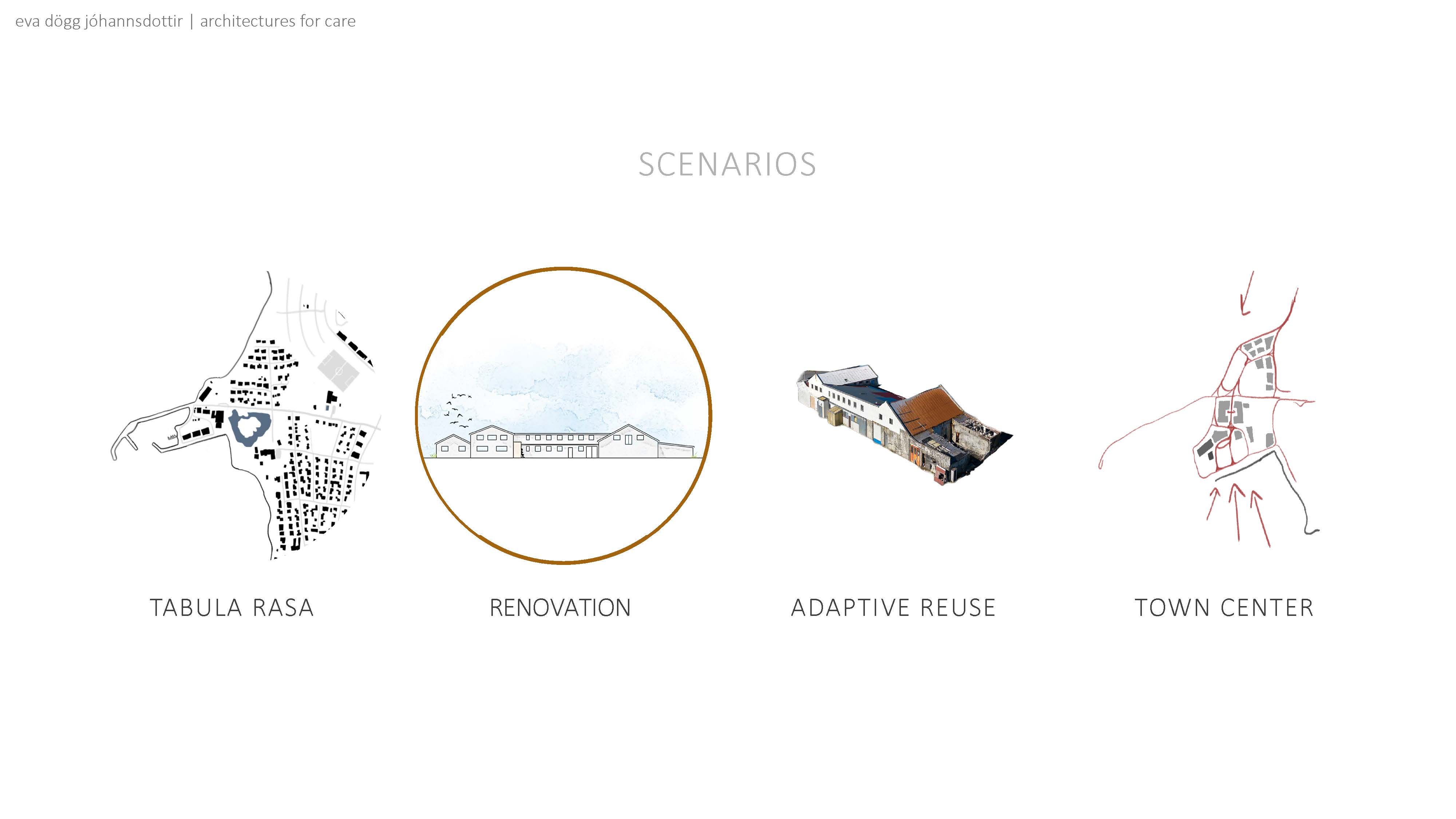

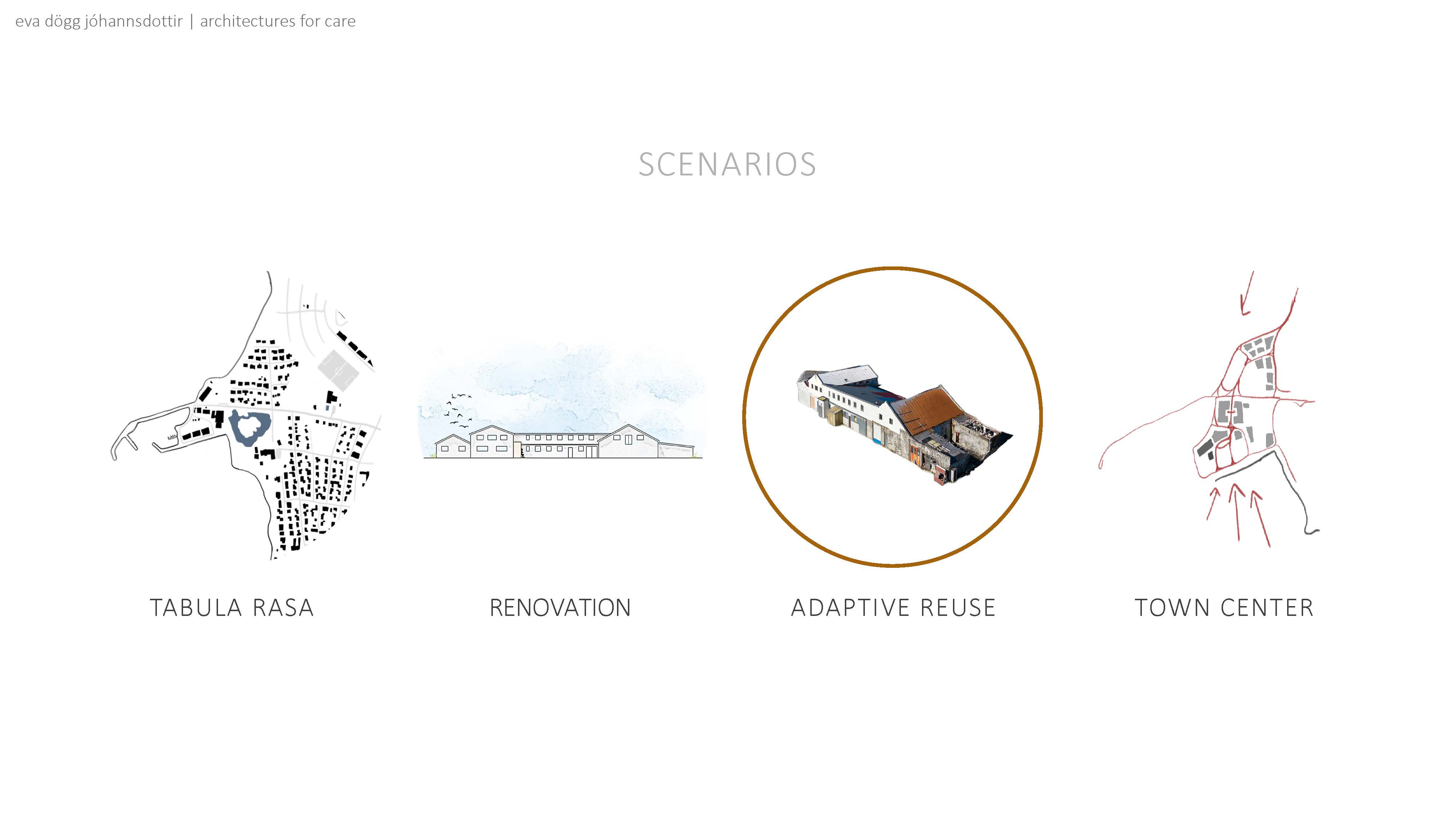

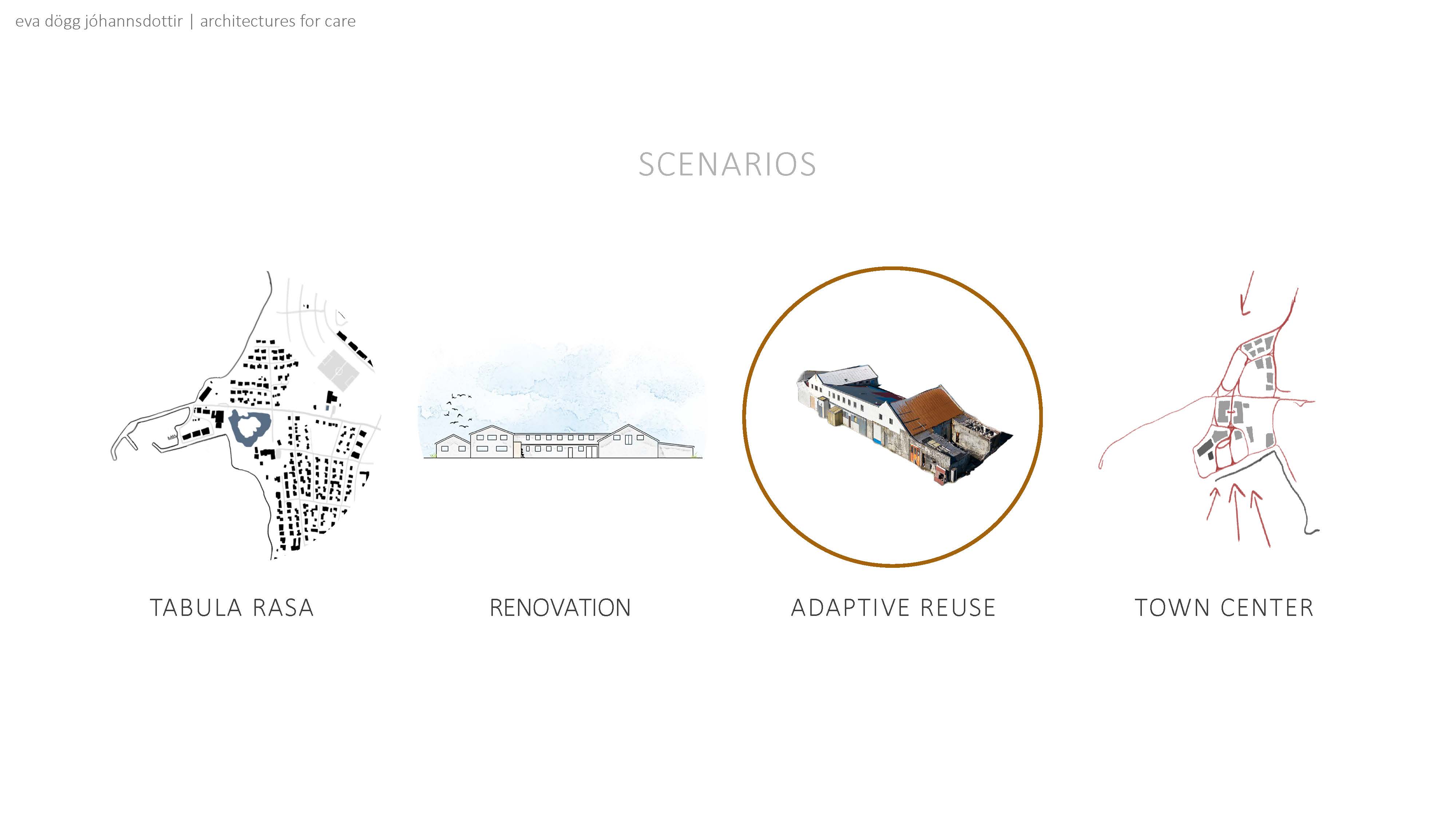

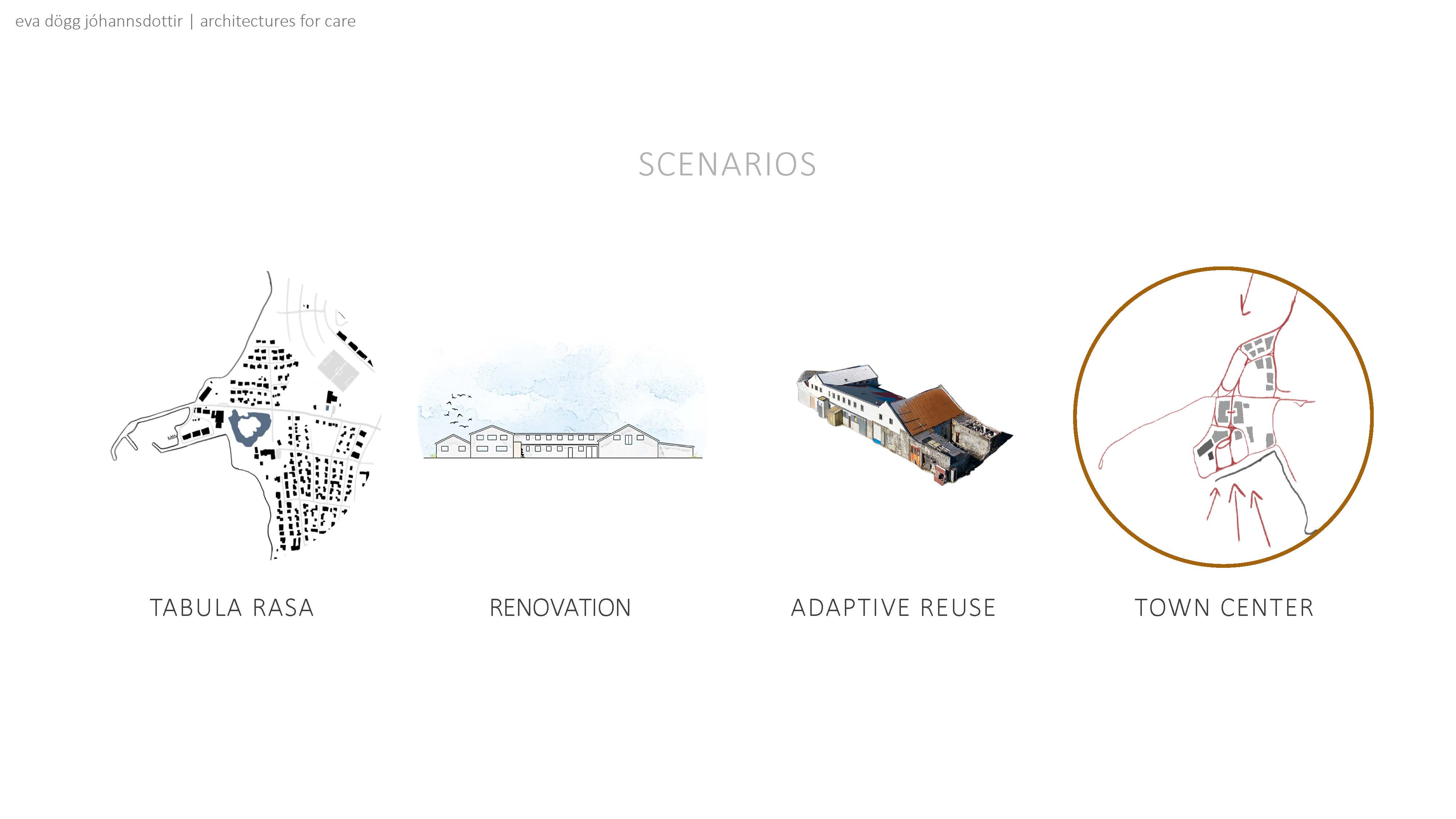

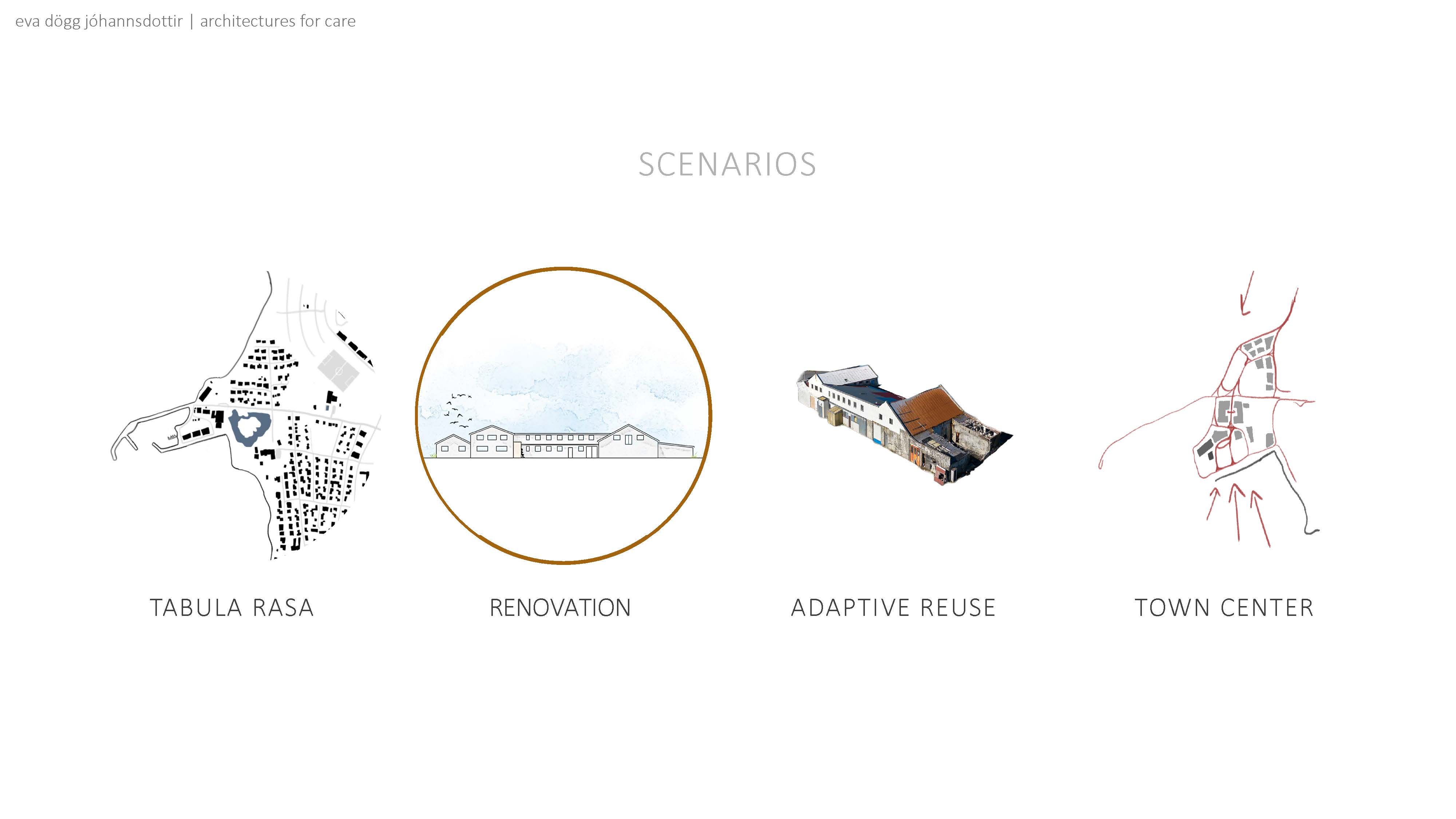

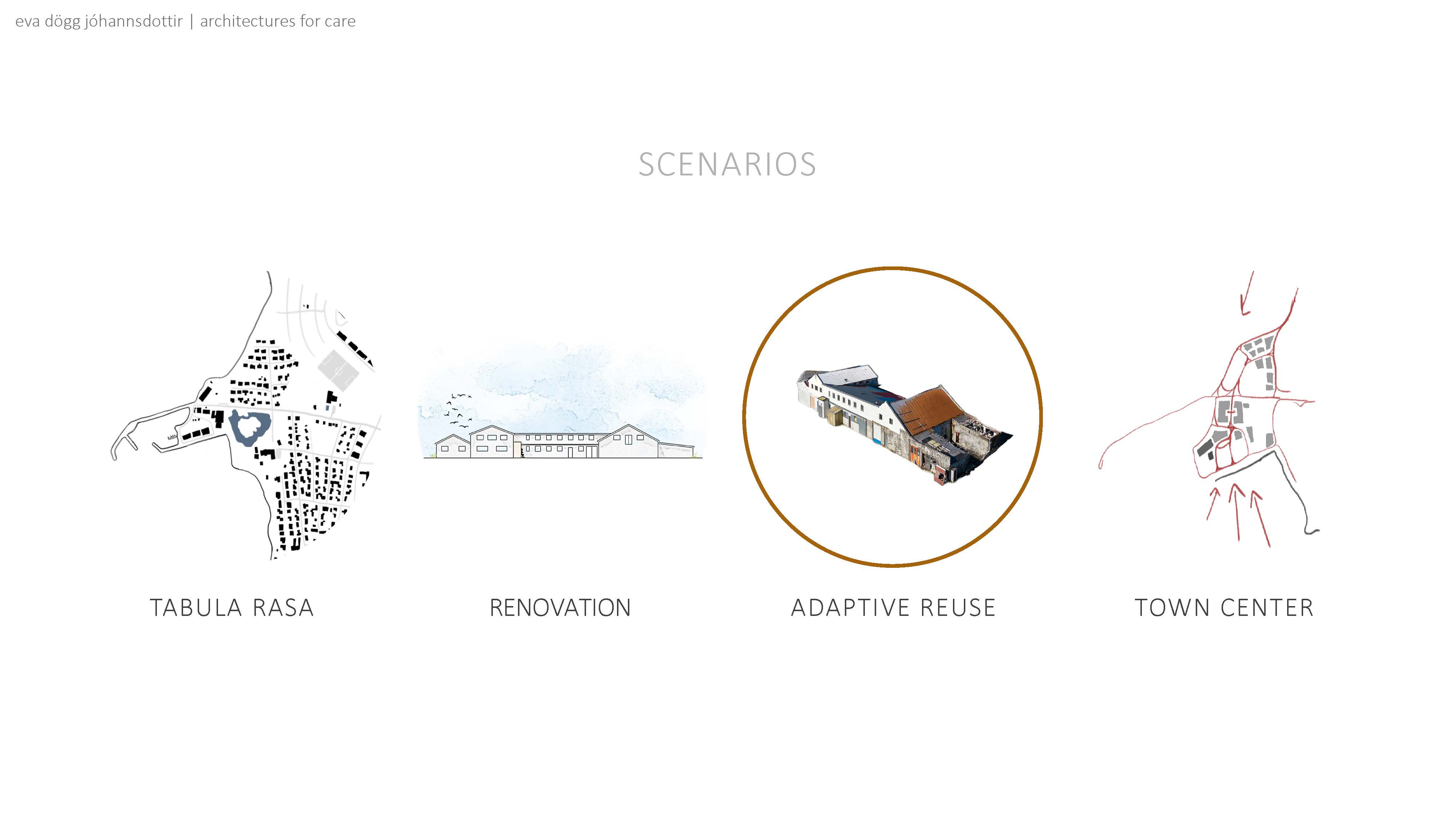

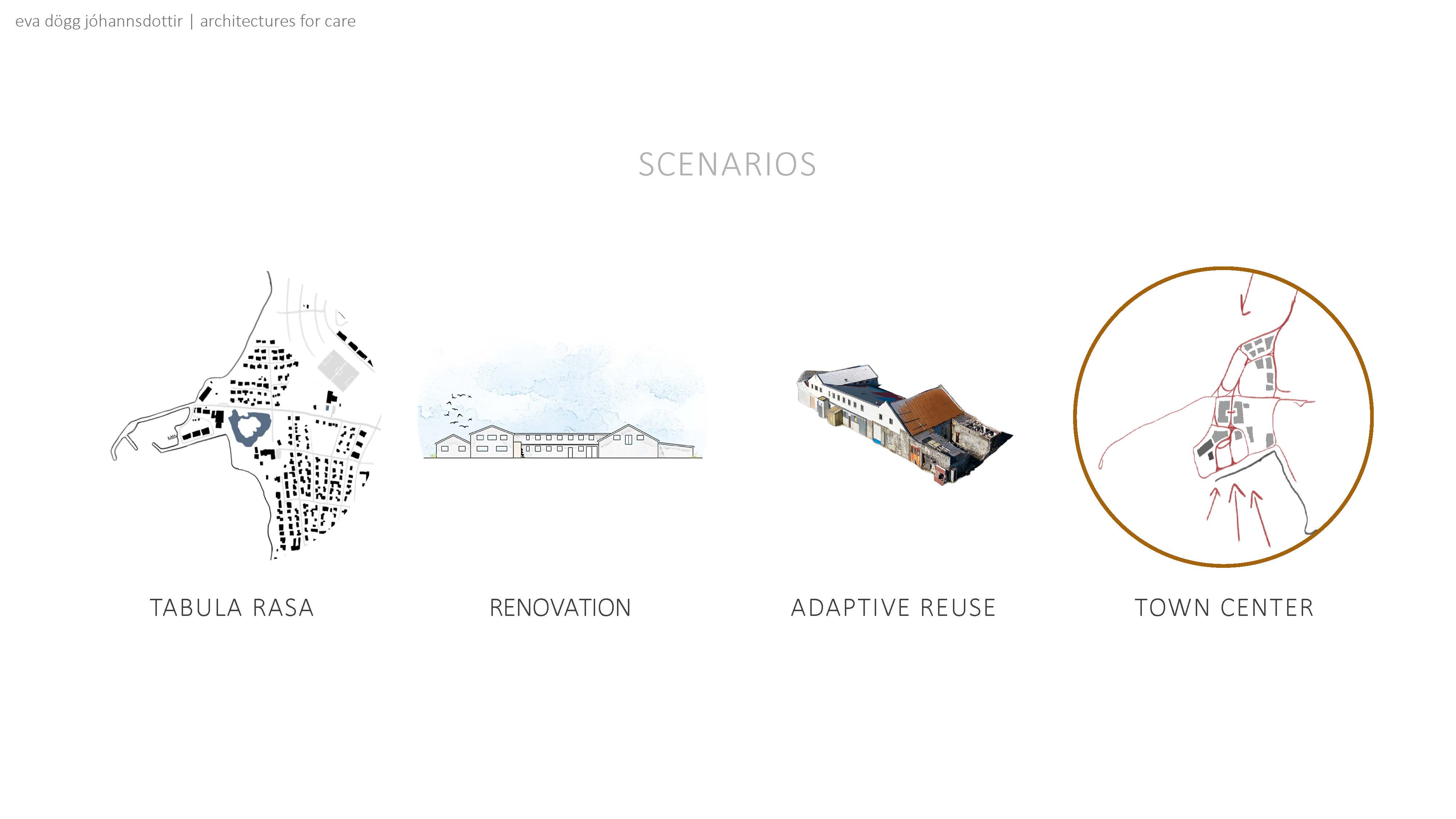

A photocollage might give a better feel for the area. As I see it, the harbour area itself has four possible futures or scenarios. We will go over these scenarios and look at examples of different

implementations.

As I see it, the harbour area itself has four possible futures or scenarios. We will go over these scenarios and look at examples of different

implementations.  Tabula rasa, Italian for blank slate,

would entail bulldozing the Frystihús. This would leave a blank slate for new development.

Tabula rasa, Italian for blank slate,

would entail bulldozing the Frystihús. This would leave a blank slate for new development. This was Vogar’s initial plan, and a direction Iceland is familiar with. We have seen a fair amount of luxury apartments with ocean views the past decade or so. Vogar seems to have moved some in a different direction as the newest news article about the plot asks for ideas which either pays tribute to the history of the area or keeps some part of the original structure.

This was Vogar’s initial plan, and a direction Iceland is familiar with. We have seen a fair amount of luxury apartments with ocean views the past decade or so. Vogar seems to have moved some in a different direction as the newest news article about the plot asks for ideas which either pays tribute to the history of the area or keeps some part of the original structure.  Then there is the possibility of renovating the building as is.

Then there is the possibility of renovating the building as is.

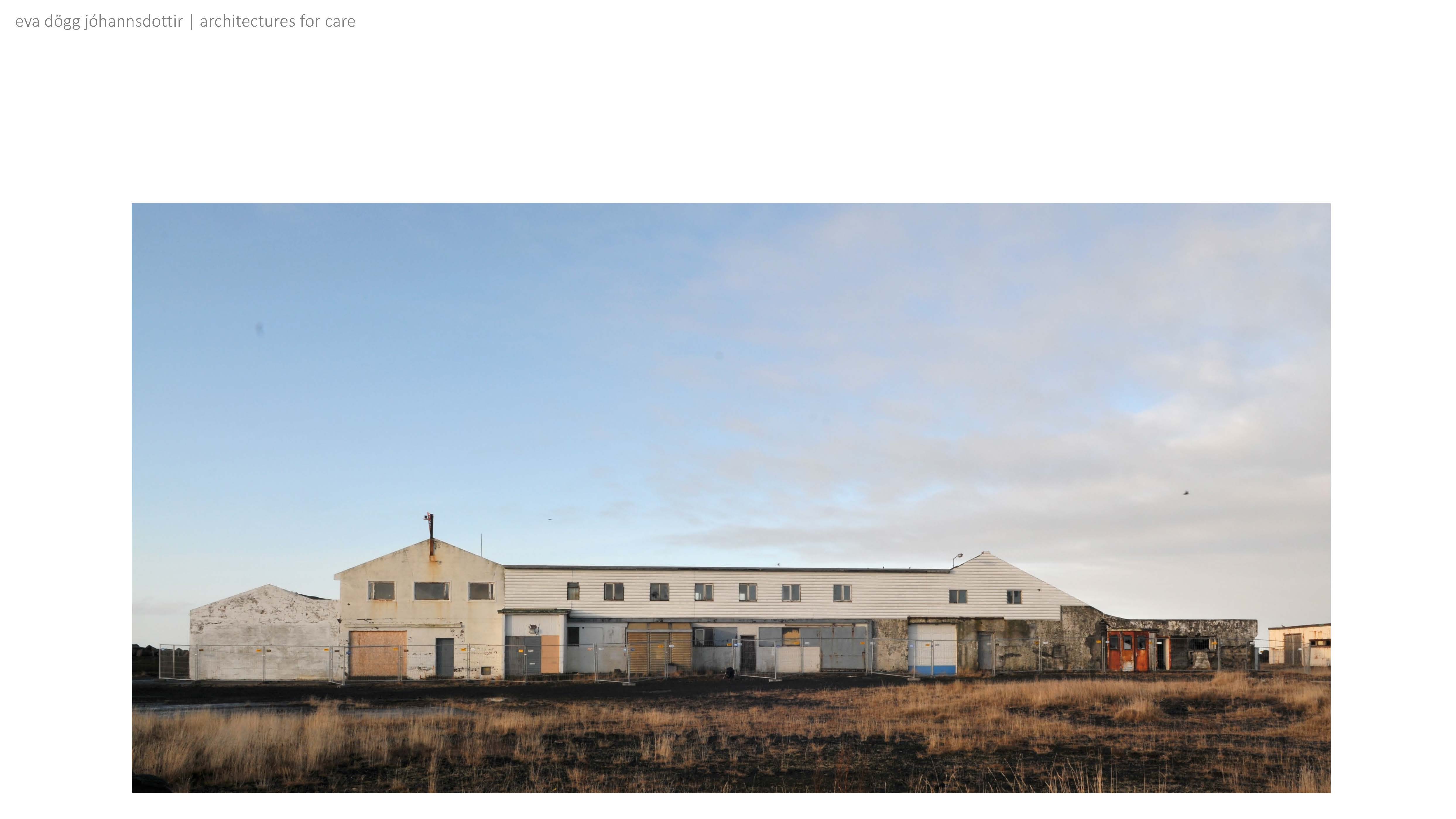

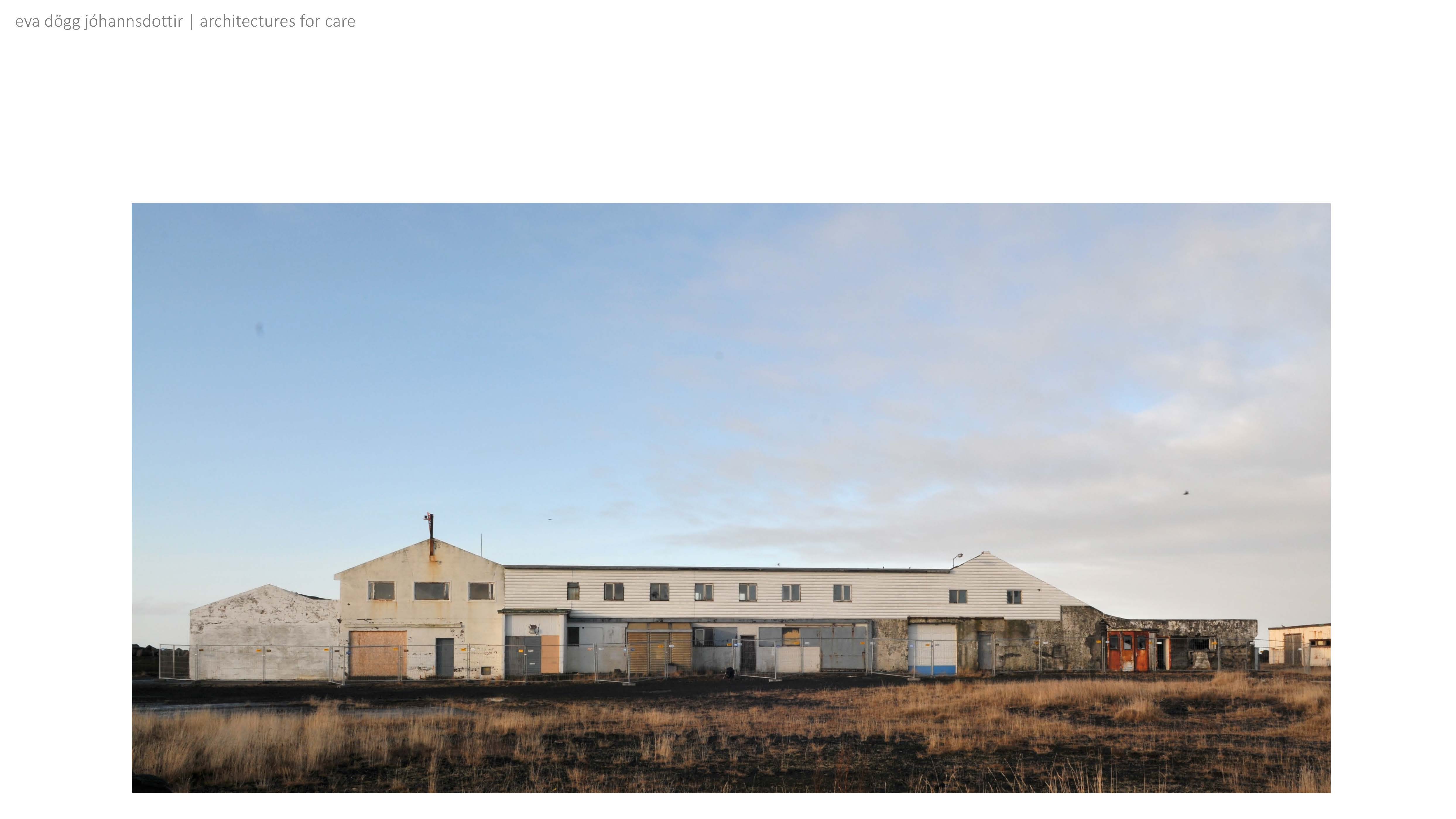

As can be seen in the images above, the building itself isn’t in great shape. An engineer evaluated the structure, and in their report, they recommended a complete tear down, mainly because of safety concerns. Minjastofnun, which is used to working with older buildings, said that “við höfum séð það talsvert svartara” or translated, they have taken on projects in worse conditions.

Currently the building is fenced off. Hopefully the building will become accessible to the next generation. Let’s look at some examples of how that might be done.

Íshús Hafnarfjarðar is an example of a low budget grassroots driven project where a fishery facility is now used as a creative workspace for everything from pottery to carpentry to sewing.

Íshús Hafnarfjarðar is an example of a low budget grassroots driven project where a fishery facility is now used as a creative workspace for everything from pottery to carpentry to sewing.  The Marshall house in Reykjavík was also grassroots driven but had a better budget to work with.

The Marshall house in Reykjavík was also grassroots driven but had a better budget to work with.  The Akureyri art museum is housed in a former dairy processing facility. The project was driven by the town and had a fairly large budget.

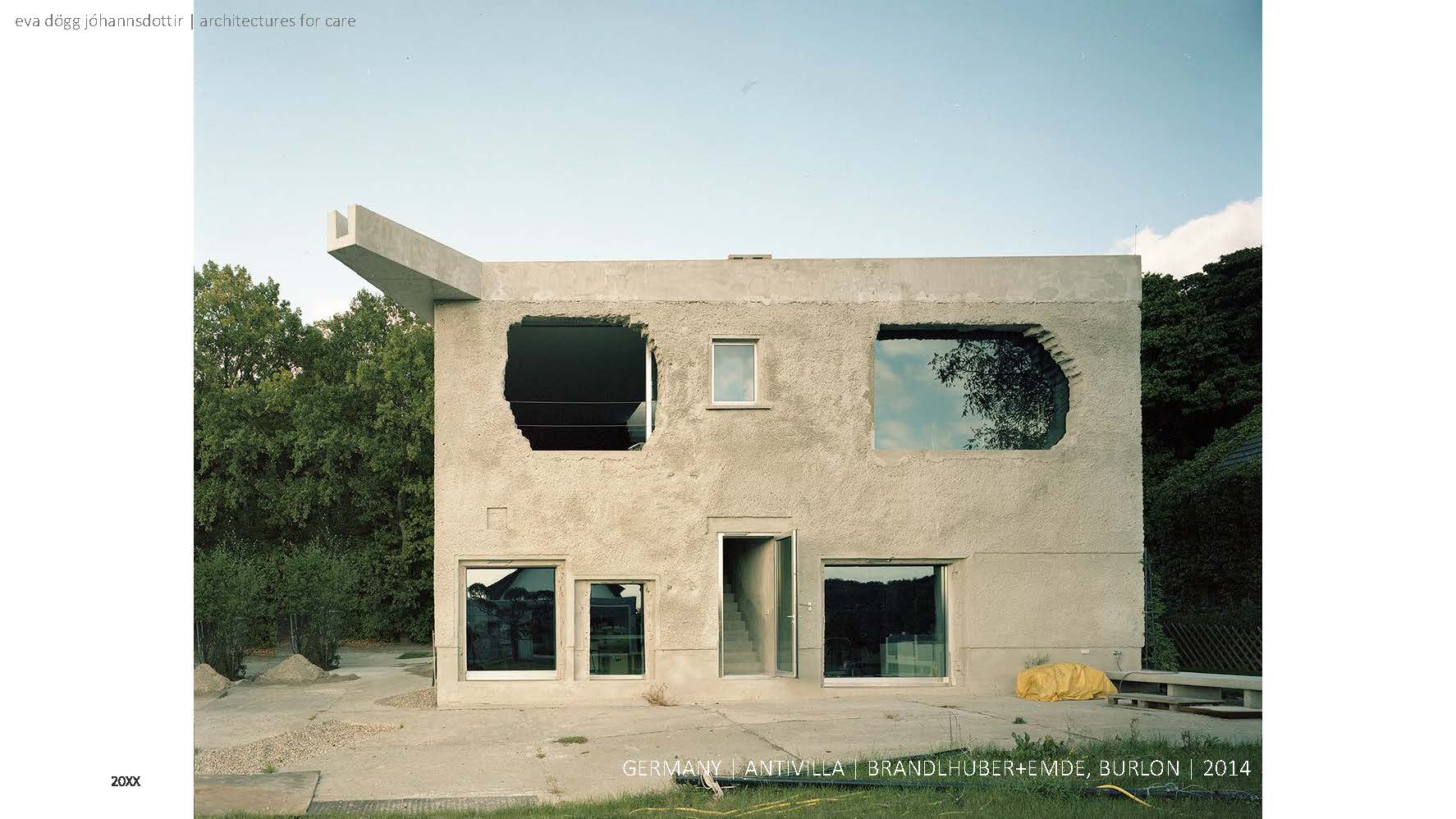

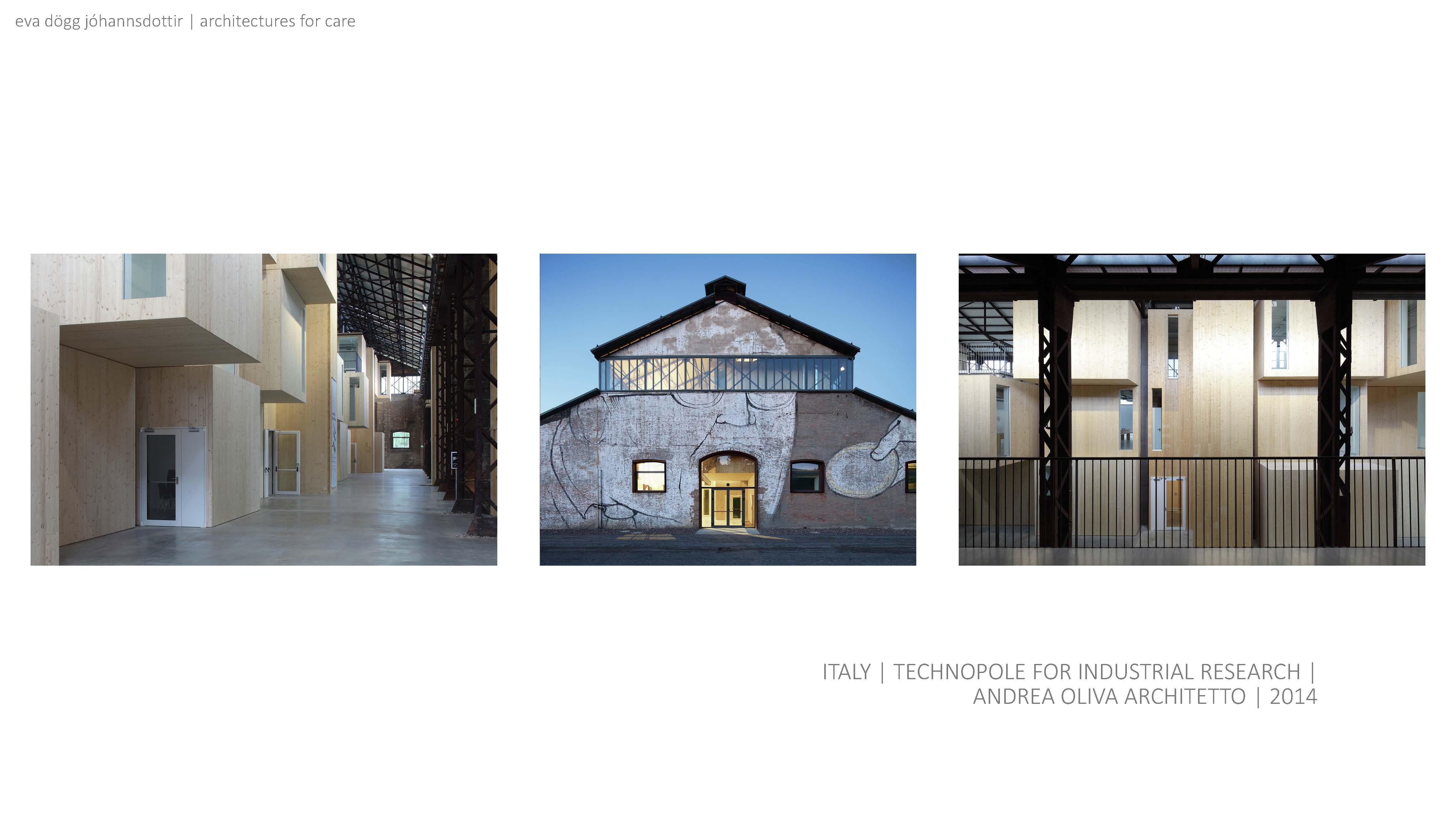

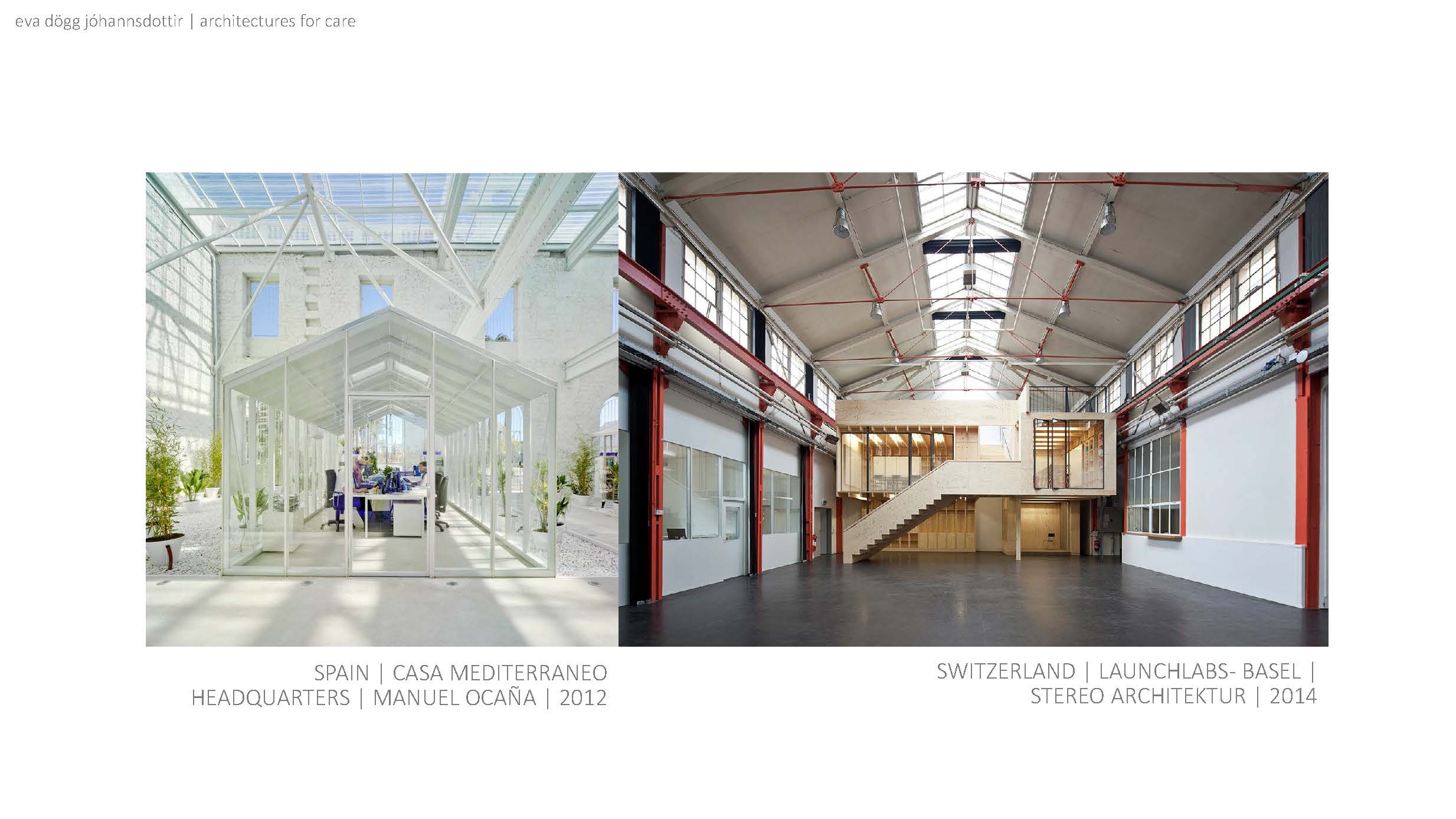

The Akureyri art museum is housed in a former dairy processing facility. The project was driven by the town and had a fairly large budget.  Adaptive reuse is an interesting concept to look into if you want to go beyond the scope of renovation. In its simplest form it entails adapting a structure to a new use. Adapting and reusing.

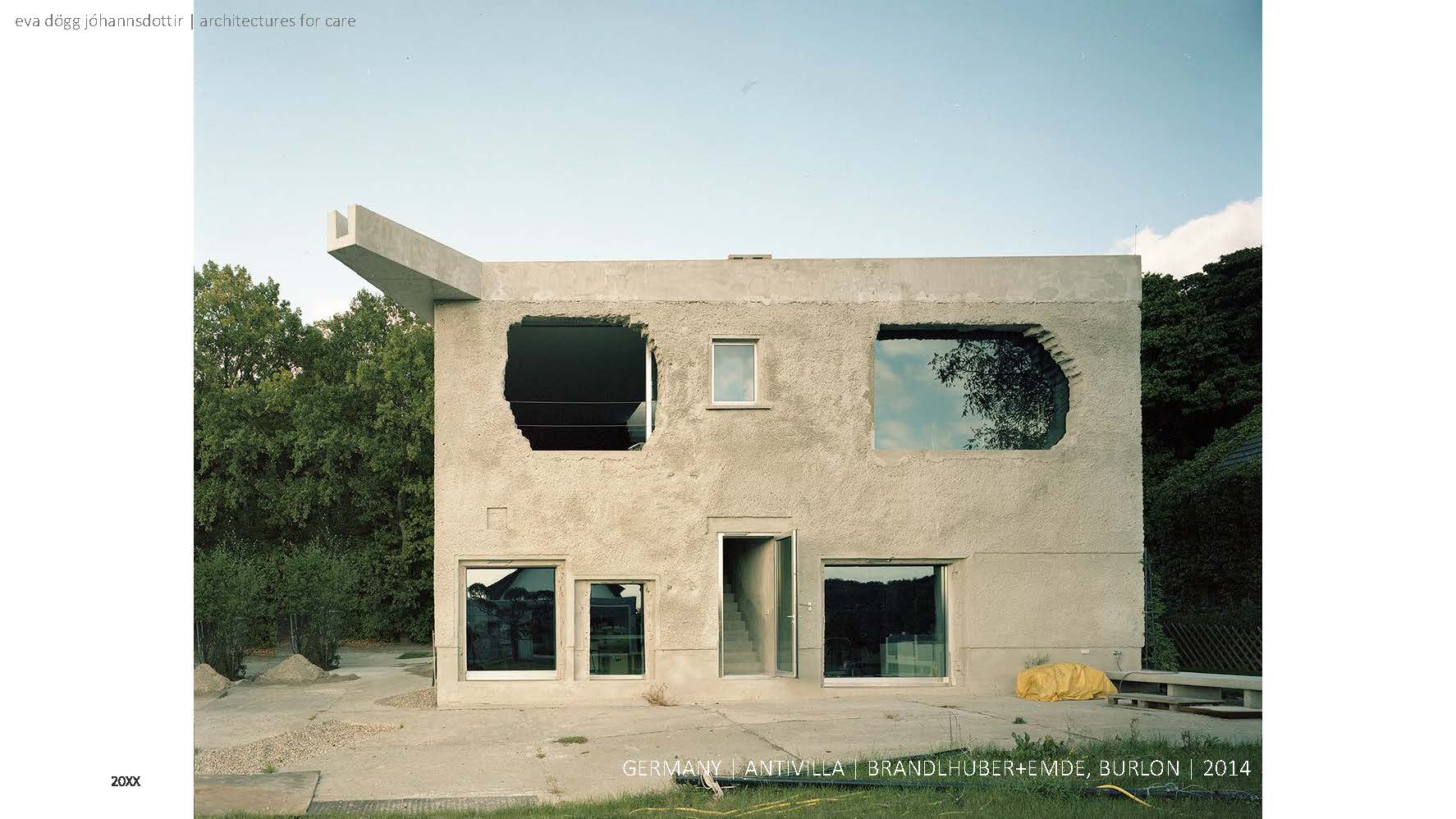

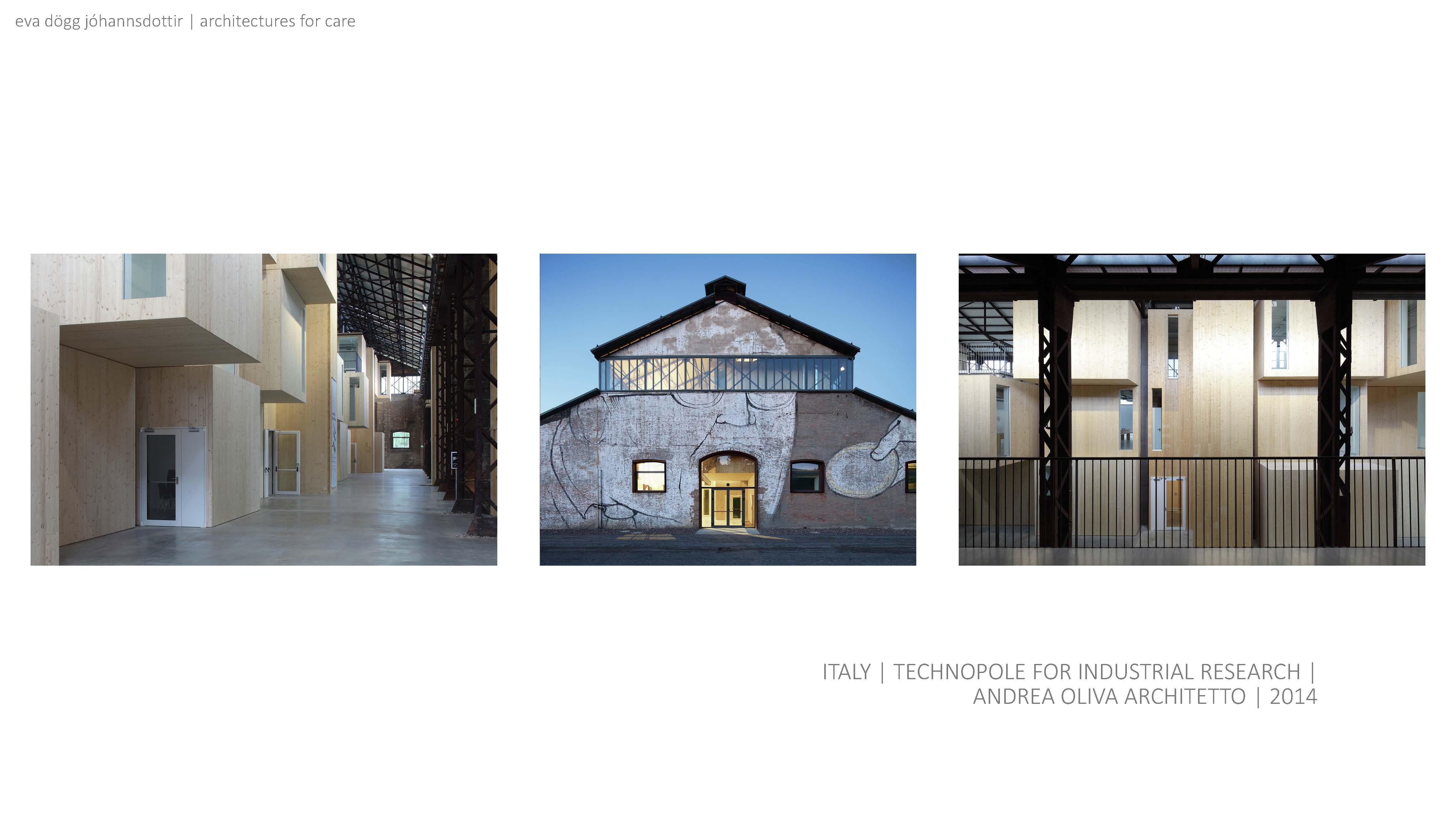

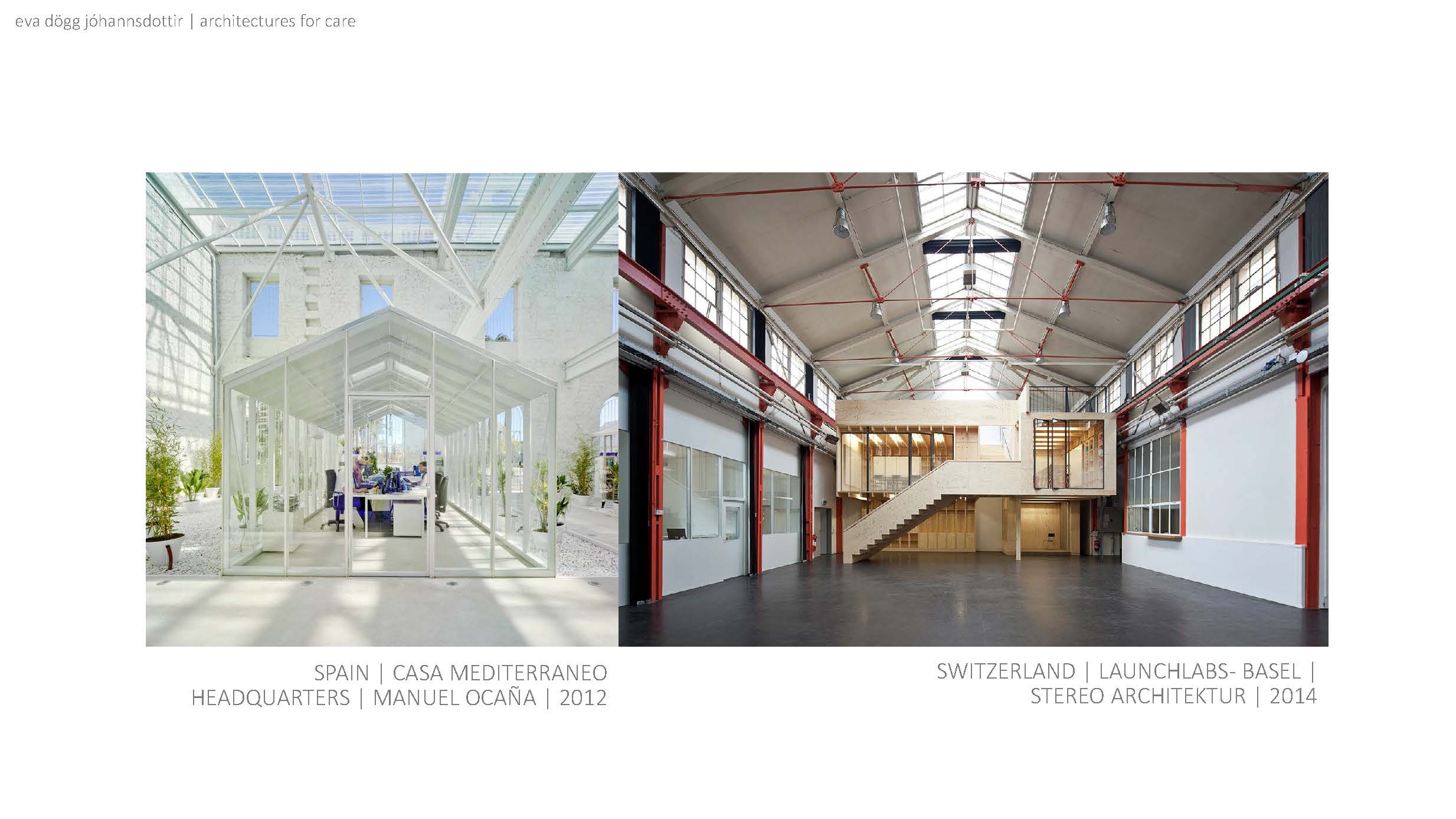

Adaptive reuse is an interesting concept to look into if you want to go beyond the scope of renovation. In its simplest form it entails adapting a structure to a new use. Adapting and reusing.

The Frystihús has gone through a multitude of evolutions throughout its lifespan. This leads me to believe that changing and evolving to new technologies, needs, and uses is at the core of the building itself. What to adapt to and how is the question going forward.

The Frystihús has gone through a multitude of evolutions throughout its lifespan. This leads me to believe that changing and evolving to new technologies, needs, and uses is at the core of the building itself. What to adapt to and how is the question going forward.

Let’s look at some examples...

The last approach I see going forward is to look at the entire harbour area. I named this approach town center in response to a lot of towns in Iceland lamenting their lack of a town center and then creating one. Within the architecture community in Iceland, some proposals and/or implementations have been deemed artificial while the general public have embraced this new era urban planning.

The last approach I see going forward is to look at the entire harbour area. I named this approach town center in response to a lot of towns in Iceland lamenting their lack of a town center and then creating one. Within the architecture community in Iceland, some proposals and/or implementations have been deemed artificial while the general public have embraced this new era urban planning. If we look at the culture line again, we can see how well suited the harbour’s location is for a town- or cultural center.

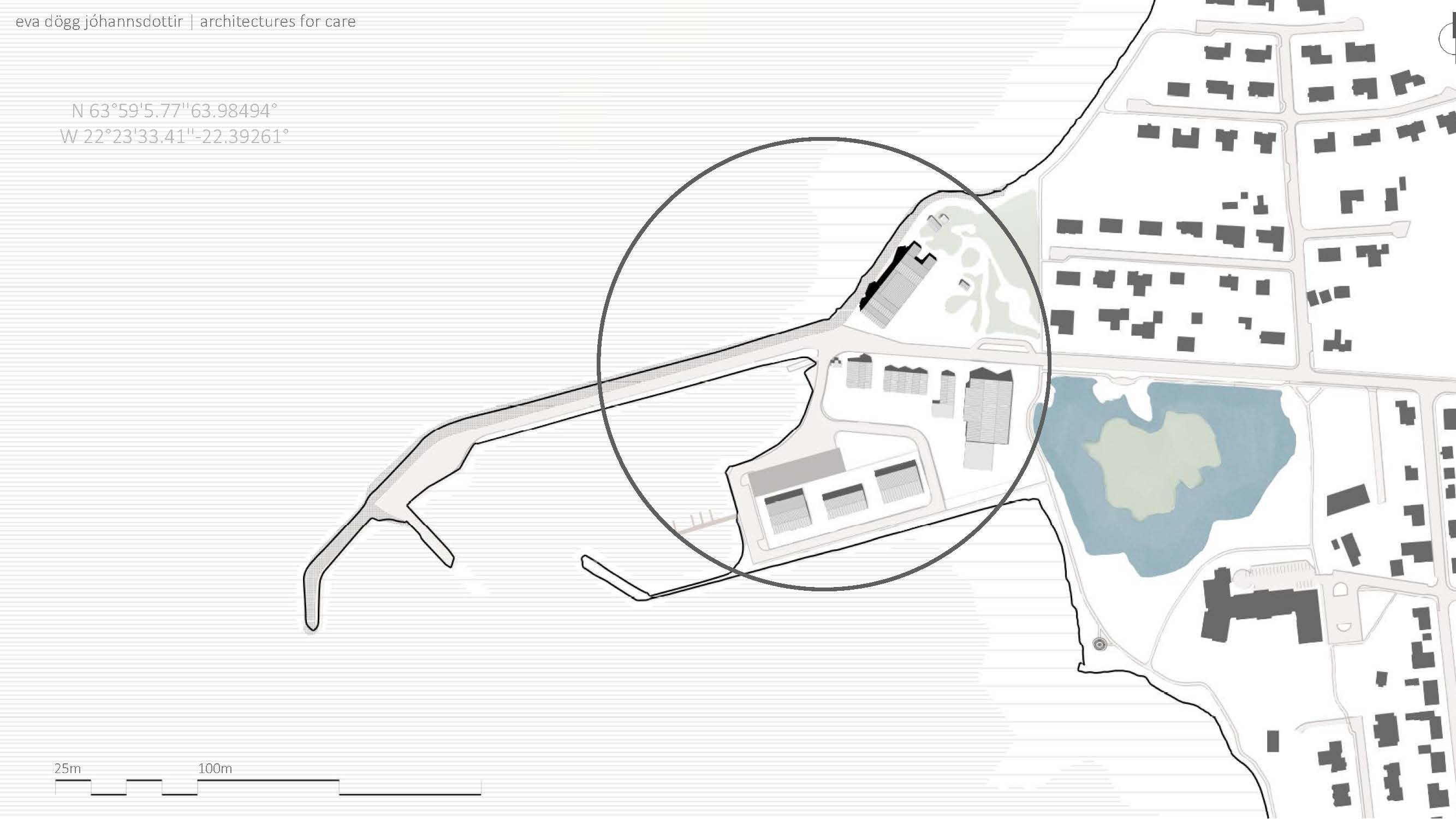

If we look at the culture line again, we can see how well suited the harbour’s location is for a town- or cultural center.  The main bounds of the area.

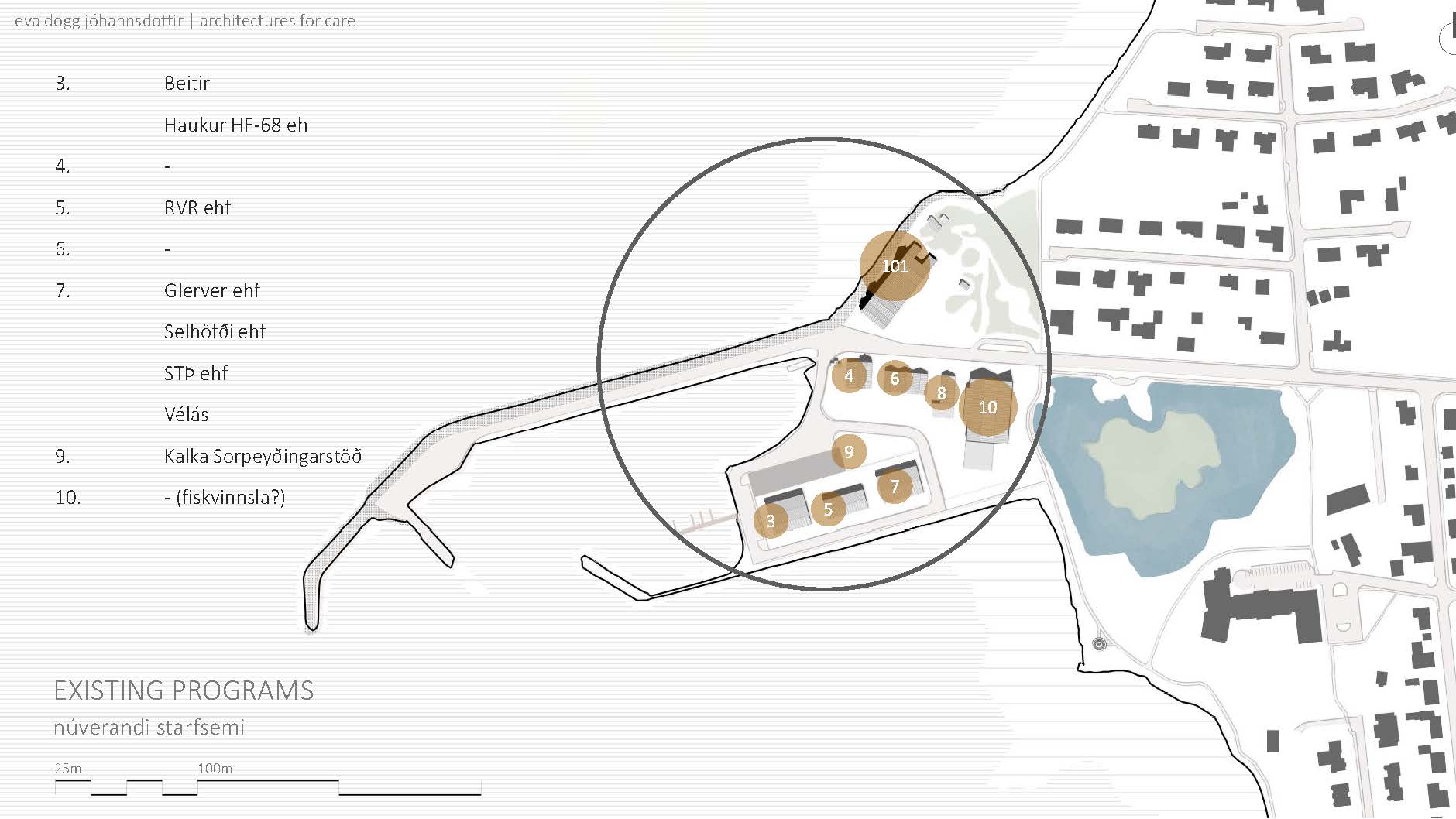

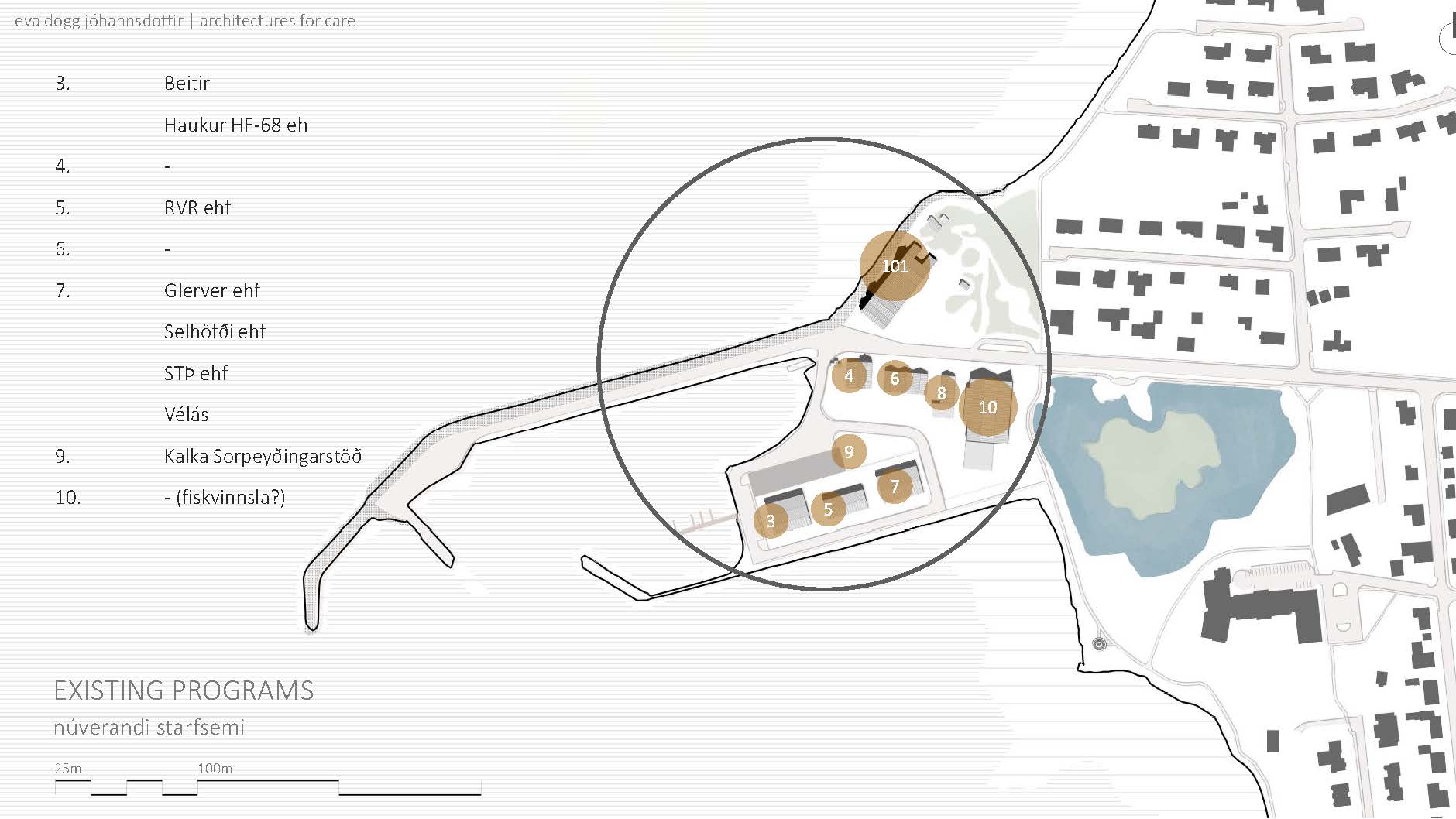

The main bounds of the area. First, we must look at what is already there. Some buildings are either not being used or I could not find information on it. The area is used mostly for light industrial work. The light grey rectangle on the north side of 3 and 5 is the foundation/construction of smaller industrial spaces which will be rented out.

First, we must look at what is already there. Some buildings are either not being used or I could not find information on it. The area is used mostly for light industrial work. The light grey rectangle on the north side of 3 and 5 is the foundation/construction of smaller industrial spaces which will be rented out.  Here we can see the main wind directions. The wind travels to the center. The size of the sections clues us into both frequency and power of the wind.

Here we can see the main wind directions. The wind travels to the center. The size of the sections clues us into both frequency and power of the wind.  Like all of Iceland, Vogar sees very little sun in the winter and almost 24-hour sun in the summer. As the terrain is fairly flat, mountains don’t cut off access to sunlight in the winter. During the summer, the sun just barely dips below the horizon after midnight coming back up an hour later. This means that even if the sun isn’t visible, it will still be bright outdoors.

Like all of Iceland, Vogar sees very little sun in the winter and almost 24-hour sun in the summer. As the terrain is fairly flat, mountains don’t cut off access to sunlight in the winter. During the summer, the sun just barely dips below the horizon after midnight coming back up an hour later. This means that even if the sun isn’t visible, it will still be bright outdoors.  The area is open, with an abundance of already established desire paths (unplanned path created by foot traffic) as well as paved vehicular and footpaths.

The area is open, with an abundance of already established desire paths (unplanned path created by foot traffic) as well as paved vehicular and footpaths. Photographs taken of the area (november 12th 2022)